ConservationIntroductionUnited Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) was created by the member states of the United Nations (UN) in 1945. China is among one of the member states. In 1982, UNESCO formed a separate committee dedicated to “Intangible Cultural Heritage” (ICH) as distinguishing it from “Physical Heritage”. Member states are responsible for defining and nominating ICH items while stakeholders are responsible for implementing policies to promote the conservation of ICH items1. According to the “Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage”, ICH refers to the practices, representations, expressions, knowledge, skills – as well as the instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated therewith – that communities, groups and, in some cases, individuals recognise as part of their cultural heritage. Instruments, objects, artefacts and cultural spaces associated therewith. 2 In 2003,UNESCO defined ICH as encompassing the following domains.3

Aside from this, the “2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of ICH” also indicates that the ICH to be safeguarded:4

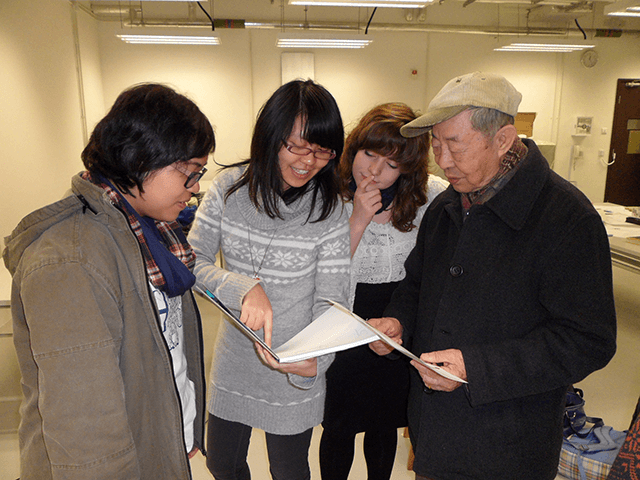

In sum, ICH can be seen as the living culture of people.5 (Lenzerini, 2011) At the same time, “since [ICH] is not [the]cultural, mechanical and neutral transmission of information from one generation to another, but a social construction, the understanding of its meaning and consequences depends on taking into account its historical context”.6(Arantes, 2007) Application for InscriptionCheung Chau Bun Festival was inscribed onto the third national list of ICH of China in 2011.7 The Piu Sik Parade alone was not registered as an ICH item because it is not the primary component of the Festival. Instead, the entire Cheung Chau Bun Festival was inscribed as an ICH item since the inscription mechanism is limited to the main title element of cultural heritage.8 Curator CHAU Hing-wah, the curator of Intangible Cultural Heritage Office, explained that "ICH covered a wide range of subjects and was hard to define. Whether a cultural heritage is inscribed depends on the domain chosen for the Inscription application. For example, if the Piu Sik Production were to inscribe as an ICH item, it would be registered under the category of 'Traditional Handicraft Skills'. But if it were to apply as a folk religion, it might be inscribed under the Folk Customs category. A UN member state, like China, has to call for nomination from the entire country if it wants to officially list a cultural heritage item on the national list of ICH. Every province, including Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (which is equivalent to a province in this respect), can pick and nominate different cultural heritage items for the national list of ICH. For that reason, the nomination is a government level undertaking that requires the input from community associations such as the Cheung Chau Bun Festival Committee. The inscription process begins with the call from Ministry of Culture of the People’s Republic of China. The Home Affairs Bureau, which is responsible for the conservation of cultural heritage, will then assign the Leisure and Cultural Service Department to select and nominate cultural heritage items. Next, experts will be recruited to evaluate whether the chosen items meet the criteria of the national list of ICH. A few requirements on the inscription application, such as 'what is the significance of the item', 'how does it pass on local heritage', and 'what is its impact to the society', are particularly critical. Hence, the experts must ensure the nominated item fulfilled the criteria".9 (Figure 1) The Cheung Chau Rural Committee initiated the inscription application of the Cheung Chau Bun Festival for the national list of ICH with the intention of promoting the Festival. Back in those days, Mr. CHAU Hing-wah established a working team and invited Prof. CHOI Chi-cheung and Dr. MA Muk Chi from the History Department at the Chinese University of Hong Kong to assist in the application. And based on his research, Prof Ma was the chief author of the application proposal. Later in 2009, the Ministry of Culture of the People’s Republic of China issued a memorandum calling the team for application submission. At the same time, the Hong Kong government entrusted the South China Research Centre at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology to conduct research surveying the intangible cultural heritage items in Hong Kong from 2009 to 2013. Since no relevant documentation or archive was available beforehand, the research centre adopted an anthropological research approach and collected first-hand information through interviews and oral history. In 2014, the centre published the research result, concluding a total of 480 ICH items classified in line with the five domains defined in UNESCO’s 2003 Convention.

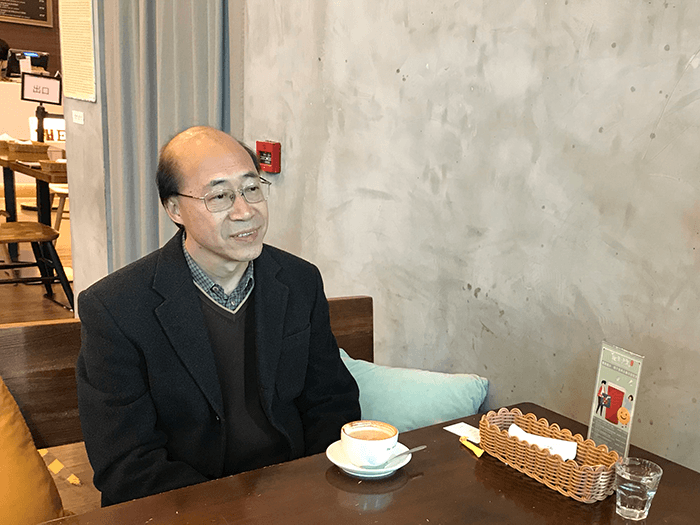

(Figure 1) Curator Chau Hing-wah. Photo by Cissy Chan (2018) Application ProceduresCurator CHAU Hing-wah, the curator of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Office, commented that "the expert team did not stress the importance of the Cheung Chau Jiao Festival based on its century-long history. Instead, they concentrated on the conservation and inheritance approaches of the Cheung Chau Bun Festival as a whole. As the strategy to pass on and let more people know a heritage in the next five years is the essence of any conservation project, the application explicated how the ritual has been conserved and inherited over the last century by thoroughly describing the origin, details, and the system of inheritance of the Cheung Chau Bun Festival. After various civic organisations had supplemented and reached consensus over the content, the Cheung Chau Rural Committee endorsed the proposal and submitted it to the LCSD’s expert team for a professional assessment. Once the expert group acknowledged the quality of the item is on par with the criteria of the national list of ICH, the director of LCSD co-signed the nomination with the Cheung Chau Rural Committee and submitted it for the Home Affairs Bureau’s approval. Finally, when all the papers and supplements were ready, the nomination was sent to the Ministry of Culture of the People's Republic of China. In that year, the Ministry of Culture of the People's Republic of China received over a thousand nominations from different provinces and administrative regions in China. It then recruited a group of professionals to evaluate the submissions. That is why the Ministry of Culture only released the final result in 2011. The involvement of numerous government departments and the lingering process shows that the ICH inscription application is much more than a civil initiative. An ICH item could only be inscribed onto the UNESCO’s list of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity after being inscribed on a national list of ICH. There are concurrently two lists of ICH in UNESCO, namely the 'Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity' and the 'List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in Need of Urgent Safeguarding'. Since the two lists are prepared by UNESCO and are separate to the national list of ICH, the Cheung Chau Jiao Festival is thus not inscribed on either of the UNESCO’s lists. Nevertheless, the national and local ICH listings are both instituted as per the UNESCO’s Convention passed in 2006. The Convention requires its member states and their local government to protect the relevant ICH items. Therefore, every member state has to set up its listing as minimum protection to ICH items."10 China, for example, has established a four-level pyramid system from the state government at the top, to the provincial government, city government and to the county government level at the bottom. For that reason, a national ICH item has to go through applications across all four levels. For instance, a county government may only nominate a few ICH items to a city government. A city government may, therefore, receive dozens of ICH nominations from various counties. City governments are then responsible for gathering and relaying the submissions to the provincial government. Provincial governments will then select the most prominent ICH items for the State Council of the People's Republic of China to make the final decision and announcement of the national list of ICH. For that reason, the national list of ICH is highly representative and the central government recognises its significance. Besides, provincial governments also treat the amount of national ICH items they possess as an achievement indicator of their governance. So, they tend to invest a lot of resources to conserve ICH items to gain popularity and attract tourists. Strategic Alignment“ The Cheung Chau Rural Committee did not know the exact procedures and requirements for applying to the Cheung Chau Bun Festival to become an ICH item. Therefore, we first had to liaise with the Rural Committee. From my perspective, first we had to investigate and gain a thorough understanding of the origin, content, development, and inheritance of the Festival. Abundant communications had to be made before I even began sorting information and drafting the application and by that time, there is only a month left before the application deadline. So, the most important act is to seek for assistance from an experienced person in collecting oral history. For that reason, we asked Mr. CHO Chau-ming, the assistant to the Chairman of the Cheung Chau Rural Committee, for his help. Since he was familiar with the key persons in the relevant groups in the region, he helped a lot with inviting them for interviews and filming. We invited scholars to fill in the inscription application in accordance with the guidelines provided by the Ministry of Culture of the State Council. At the beginning, we all thought that it would be a simple matter. Hence, we navigated to the UNESCO’s website and read through the criteria as proposed in the Convention, and structured the application accordingly. However, we realised that the criteria of the Chinese government were different from those of the UNESCO. Unlike the categorisation of the UNESCO, the Chinese government has ten categories. We did not know which category should we choose, nor why the Chinese government categorise in those ten options. We even wondered whether the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region should classify ICH items according to the ten categories. At that time, four items were applying for inscription. Prof. LIU Tik-sang handled two while a mainland scholar undertook the other one. According to the national list of ICH of China, Cheung Chau Bun Festival is inscribed onto the third national list of ICH that falls under the 10th category– 'Folk Customs'. Neither does any of the other nine categories nor any of its content relates to religious ceremonies. Hence, it was necessary to adjust the focus of the ICH application to fit in with the criteria and its categorisation as such a sacred ritual could not be classified as a 'Folk Custom' after all. In that regard, it was pivotal to tone the Cheung Chau Bun Festival as a folk custom instead of emphasising that it is a type of religious ceremony. And in fact, culture is a 'living' and 'organic' phenomenon; some religious activities in some communities will diminish the rituality of certain types of religious ceremonies over time. Take the Taoism ritual by the Hai lu feng clansmen as an example, it is a ceremony with a strong sense of folk tradition. It is what we so-called 'bud ritual'. Other than that, there was also a spiritual ritual called 'tongji ' (child medium who communicates with the dead). It began to decline around twenty years ago as there was simply no one inheriting the ceremony. I suppose no one would treat it as an ordinary culture. But if one were to research about Hong Kong culture, it would be an essential ritual to investigate. And because 'tongji ' did encompass the unique culture of a community, one had to explain its specificity if it were to be the core element of an inscription application. However, does that mean we have to pass on the feature of this local heritage? Because inheritance is a crucial criterion for an ICH item, it is impossible to inscribe a heritage item that is not possible to be passed on. Then, if one were to pass on the heritage, would one be obliged to hand down all the features of the ritual? If so, how should one draft the application form for this sort of ICH item? As it would be seen as religious or superstitious if one would expound on the full content faithfully .And how could it fulfil the requirements and criteria of the national list of ICH of China? By contrast, the Piu Sik Parade and the carnival activities in the Cheung Chau Bun Festival all serve for the folk, religious custom. Therefore, we could stress the importance of the religious rituals to the Festival. If you interview the islanders, they are certainly going to maintain that the ritual is the essence of the Festival as their cultural identity is found upon the religious belief. Therefore, not only are the older generations in the community conscientious to keep to the traditions of burning incenses, worship and the rituals, but the younger generation is also starting to care.”11( Figure 2)

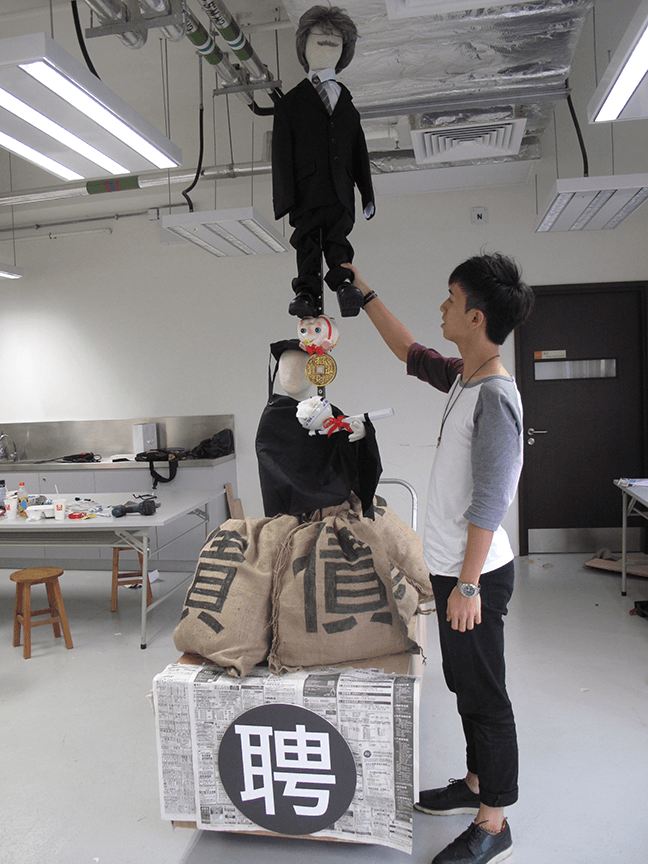

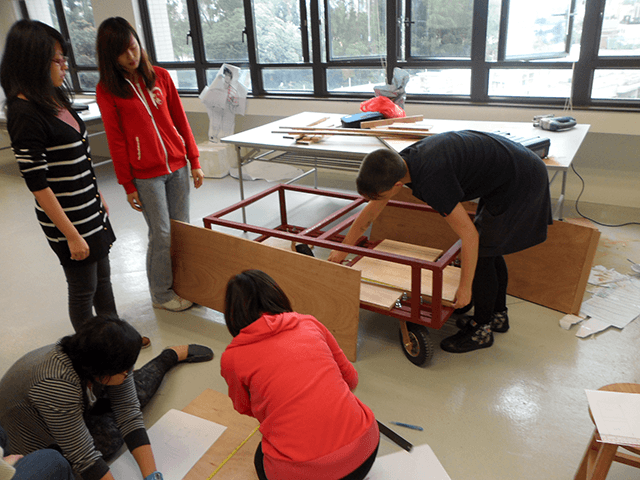

(Figure 2) Dr. Ma Muk-chi. Photo by Cissy Chan (2018) Inheritance and ConservationThe Piu Sik Masters in Cheung Chau are all over sixty or seventy, and most of them have already retired. Every street association and group on the island is facing the crisis of 'succession gap' – a widespread issue among most traditional crafts in Hong Kong. In the inscription application for Cheung Chau Bun Festival, the working team had to propose a five-year conservation plan. After the Festival was successfully inscribed, the conservation of the Cheung Chau Bun Festival became the key assignment for the festival organising committee. The committee cannot only safeguard some of the niche elements of the Festival, that is the conservation cannot only focus on the Piu Sik. Instead, the committee has to conserve the entire Festival in a broad sense. For example, it had to commission non-profit organisations to promote, publicise and deepen the general public's knowledge of the Festival. On the other hand, it had to collaborate with scholars to research as thoroughly as the work of Dr. MA Muk-chi. Then, The Conservancy Association Centre for Heritage, Dr. Wong King-chung was to promote and popularise the Festival. Under this circumstance, the conservation of Piu Sik was outside of the scope of our primary focus. Therefore, he could only attempt to promote and support the inheritance of Piu Sik production by organising some activities which contained the introduction and interview of Piu Sik frame Master WONG Shing-chau as a sideline. The chapter of 'Examining the Direction of Preserving Hong Kong’s Intangible Cultural Heritage: A Case of Hong Kong Cheung Chau’s Bun Festival'12 in A Collection of Speeches and Papers from the Seminars on Hong Kong History provided a detailed introduction on this context. The author, Dr. Wong King-chung, took Master Wong as an example and introduced his transformation and experience of changing profession from a blacksmith to a Piu Sik artisan. In addition, The Conservancy Association also organised an exhibition titled the ‘Exhibition of Works by Master Craftsmen and the Apprentices’ with some workshops held in the secondary schools. In the show, the Association invited Master Wong to teach and demonstrate the procedures of Piu Sik making as well as the iron hammering technique for the Piu Sik frame. By virtue of Master Wong’s generosity of unveiling the precious archives of his family business, the exhibition’s catalogue also showcased the historical information about the three generations of Wong's family.13 There are no deficiencies of popular literature about the Cheung Chau Bun Festival. The reports by the Buddhist Wai Yan Memorial College are among the more systematic research, which comprised local community surveys and research, the students of the college provided thorough and detailed information about the Festival. The report even received excellent grading under the secondary school curriculum.14 More importantly, the students promoted the conservation of the Cheung Chau Bun Festival throughout their survey and research. Besides, there are still numerous outstanding projects that investigated the ICH, folklore traditions and the general knowledge of the rituals. The Relationship between Intangible Cultural Heritage and Cultural Identity -- Tracking Down the History of Cheung Chau Jiao Festival and Exploring Intangible Cultural Heritage –Conservation Value and Development of Cheung Chau Jiao Festival15 , a hundred-page report, both written for the Hong Kong Secondary School Cultural Competition, are yet another critical research output for the Cheung Chau Bun Festival. Then, the Case Study of Local Heritage Studies: Cheung Chau Jiao Festival16 , a teaching plan tailor-made for high school teachers, is an archetypal resource on the same topic for teaching and learning. Not only does it provide historical information and examples, but also the experience and advice on the conservation of ICH in Hong Kong from renowned scholars like Mr. CHAU Hing-wah, Prof. CHOI Chi-cheung & Dr. MA Muk-chi. The former Cheung Chau Bun Festival Organising Committee had been issuing The Carnival Parade Catalogue annually. By documenting the activities of the annual Festival, the catalogue serves as a crucial first-hand research resource. The issue even reprinted a report about the cultural background and activities of Cheung Chau Bun Festival written by foreign press in 1953. It testified that the Cheung Chau Bun Festival had already been promoted to the international audience as early as the 1950s.17 (Figure 3) (Figure 3) The Carnival Parade Catalogue In 2016, the Intangible Cultural Heritage Office re-purposed Sam Tung Uk Museum as the Hong Kong Intangible Cultural Heritage Centre. Apart from the duties of verifying local ICH items continually, conducting surveys, and managing the archive, the Intangible Cultural Heritage Office also rolled out a special subsidy scheme in 2019. The project encourages the community to partake in the protection of ICH items. Through the “community-driven” ICH funding scheme, the Intangible Cultural Heritage Office provides supports for institutional and individual applicants in the promotion and research of ICH items. More substantial funding will also be given out after reviews. The scheme intends to deepen public involvement and diversify channels and approaches in conservation through community participation. These endeavours are also named as crucial conservation strategies in UNESCO's Convention. Regarding the inheritance of Piu Sik making, the Academy of Visual Arts at Hong Kong Baptist University has incorporated traditional crafts in a course titled “Hong Kong Traditional Handicraft and Transformation” under its undergraduate curriculum since 2010. In 2012, the Academy invited Master AU Lay-wei, the 80-year-old Piu Sik Master craft from Cheung Chau Hing Lung Street Kai Fong Committee, to introduce the making of Piu Sik. Students were then given assignments to build brand new Piu Sik carts and steel frames as well as to design the costume of hovering kids. The course and the Piu Sik production workshop lasted for a semester. By the end of the semester, the student-built Piu Sik sets went on a parade at the pedestrian area in Mong Kok. (Figure 1-8; Video 1 and 2) The students also joined the parade team of Hing Lun Street Kai Fong Committee as volunteers in the subsequent academic year. (Figure 9) One of the students even went on to learn advanced Piu Sik craftsmanship from Master Au outside of the class. This student can be regarded as a freshman from outside of the island who is capable of producing an entire Piu Sik set. This case was indeed an extraordinary inheritance experience in the field of Piu Sik making. (Video 3) (Video 1) (Video 2) (Video 3) Funded by the Hong Kong Jockey Club, the Hong Kong Arts Centre and Lingnan University jointly organised a knowledge transfer project titled “Jockey Club ICH+ Innovative Heritage Education Programme – Pass it On Course”. Through workshops and courses in high schools and universities, the project aimed to heighten high school students’ and the public's knowledge of ICH. The four-and-a-half-year project launched in August 2018. The overall operation of the two core programmes in the project, “Pass It On@Secondary” and “Pass It On@Tertiary”, are overseen by Prof. LAU Chi-pang from the History Department at Lingnan University. And the backbone of this project is the traditional artisans, masters of ICH craft and contemporary art practitioners and trainees (although this scheme does not include the Pui Sik). Extended DiscussionInitially, the government led the conservation of ICH items in Hong Kong. First, the government established the Intangible Cultural Heritage Office to carry out a survey of ICH items and apply for their registration. The Intangible Cultural Heritage Office then found the Hong Kong Intangible Cultural Heritage Centre to formulate strategies and directions for the conservation of ICH items. At the same time, comprehensive research on the history of traditional crafts and ICH undertook by the academia as well as an active involvement of non-government organisations have built up a framework and platform for the inheritance and conservation of ICH items. However, regardless of these positive developments, there remain many questions about the future of conservation. The issue regarding the conservation of the Cheung Chau Bun Festival was mentioned in the above paragraph on “Application for Inscription”. Dr. MA Muk-chi pointed out that religious rituals are core to the Festival. Some ceremonies started to diminish some twenty years ago. For example, 'ji tong' failed to be passed on due to the lack of successors and the ritual disappeared. The reason why the rituals of the Bun Festival prevailed is built on the folk religion in Cheung Chau as well as the community’s identification with the religious belief that has its core focus on the protection of the communal space, the making of prayers for rewards and blessings for the community. The UNESCO’s Convention defined ICH items as “living” cultural artefacts, meaning that an ICH item is ever-changing in its cultural ecology. The fasting tradition during the Cheung Chau Bun Festival is a typical example in this regard. The fasting tradition was broken due to the influx of tourists; the use the local traditional Festival to develop tourism could trigger a dilemma. But in the end, the endeavour for inheritance and conservation superseded the core values of the religious ritual. So, on that account, what is the essence of conservation and how should it be protected? At the same time, how do we define such essence? In terms of the Piu Sik Parade, Cheung Chau has developed a distinctive form in comparison to the variant in Foshan. As opposed to the government-driven Foshan PiuSik which has become a folk custom that has discarded the religious elements, Cheung Chau Piu Sik has retained the religious ceremony, composed collectively by community organisations and neighbourhood associations (despite the Festival has strategically applied for ICH inscription under the category of “Folk Customs”). Curator CHAU Hing-wah described, "Many Intangible Cultural Heritage has lost in different parts of China. Hong Kong is a rare place that still preserves many ICH items. For example, the Cheung Chau Piu Sik was copying from Foshan. Literature recorded that a Cheung Chau inhabitant saw a Piu Sik parade in Foshan in the 1920s. The islander then brought the idea back to Cheung Chau. For that reason, the Cheung Chau Piu Sik is clearly the result of cultural influences both ways. Before 1949, Mr. SUN Yat-sen began to apprehend that the Chinese temples and religions were all superstitious and superannuated. Therefore, the government of the Republic of China gradually suppressed folk religions. The policy was further aggravated, and all temples and religions were banned after 1949. The religious oppression was moderately loosened up only after the Chinese economic reform in 1979. Nevertheless, there are still a lot of taboos as the country’s political ideology is state atheism. In the past eight to ten years or so, we have seen a transformation towards the new ICH protection policy to let the people embark on preserving ICH items. As a matter of fact, the inscription of ICH items is dominated by the state government, resulting in a situation where the people follow whatever the government advocates. Rather than existing as pure traditions, folk traditions are gradually become tourism projects. But in retrospect, many folk religions were lost in the past few decades. How could the people preserve and inherit the folk traditions by their effort alone? If the state government did not take the lead, those folk traditions would be gone forever! To think more deeply, the current situation may mark as the initial development as no one would take the lead except for the officials. As the state has now sown the seeds for ICH preservation and inheritance, the people will slowly take over and build up an annual routine at their own initiative. This is a typical characteristic of how ICH items develop and pass on, and it is exactly the progress I wish to see. That is also why I often say that intangible cultural heritage items are living cultural artefacts. It is crucial for ICH items to 'evolve' constantly. ICH items are bound to changes with the involvement of different people and the transformation of the society. However, I hope that the essence of ICH items will remain unchanged despite all the evolution. An ICH item like the Cheung Chau Bun Festival has always been a religious ritual, and the essence of the religious ceremony lies in the people's belief in the purifying power of the deities. Hence, being the belief of the people, the ritual has to been done annually. It is comparable to the repentance ceremonies and the noon service that are critical to Taoist monks. If the essence of these rituals is not preserved, it is pointless. Besides, the ritual opera performance in the Cheung Chau Bun Festival is also a popular feature. Although the primary purpose of the ritual performance is to raise money, its entertaining quality is of similar importance as it is intended to amuse both the people and the immortals. Hence, people expect that the setting, form, and content of the performance remain the same except for exceptional circumstances to prevent any disputes."18 The Cheung Chau Piu Sik Parade features a wide range of themes and topics. Apart from Piu Sik sets in ancient costumes, various teams also adapt content from the current popular culture as their theme.; Satire on current affairs is an especially well-received theme. The “freedom of creativity” is a result of the freedom of speech in Hong Kong politics and social vibes. Moreover, the popularity of these sets among the mass media is also indirectly promoting the parade. In some occasions, a specific social issue may become the subject matter of various parade teams, leading to a collision where several Piu Sik sets are styled in and of the same costume and theme. Despite everything, Curator CHAU Hing-wah is optimistic about the conservation of this ICH item. He commented, “Folk tradition is something that has been passed on in the community. Many matters related to folk tradition are constantly evolving together with society. And in the course of evolution, many things and conditions vanish silently. For example, many handicrafts were brought to a halt due to the lack of demand and gradually become extinct. And the so-called inheritance system requires the registration of the inheritor. The national master craftsmen recognised by the state are responsible for verifying the filing of the inheritors. Once an inheritor is acknowledged as a national master, his works will be collected by many and become museum objects, and hence open up a new market. With the national recognition, and a craft gaining popularity and becomes well-known, the craftsmen’s works gain sales momentum and income creating a virtuous cycle attracting young people to enter the field. That is why numerous inheritance bases have been set up in mainland China. They allow master craftsmen to host all kind of workshops to attract young people to learn the craft. To pass on the craft is the vital mission for the master craftsmen because the state recognition prescribed that the national master craftsmen / recognised inheritors pass on his skills to his inheritors. Therefore, nationally recognised inheritors (master craftsmen) are willing to hand down their expertise as long as young people are eager to learn. This kind of cultural inheritance regulation was not originated from China. In fact, it was first implemented by the Japanese government in 1950. Therefore, the world is indeed imitating the Japanese model to preserve ICH items. Japanese people title a master craftsman as a 'Living National Treasure'. For example, a noh drama performer can only become a 'Living National Treasure' if several performers recognise him. Once a craft becomes a “Living National Treasure”, the Japanese government will offer him a subsidy of 2 million Yen a year as an incentive for him to dedicate to the passing on of his craft.”19 However, the protection of master craftsmen or inheritors is even more challenging in comparison to the conservation of tangible cultural heritage items. The latter will not unexpectedly disappear if one keeps them intact and preserve them from deterioration in museums or storage. By contrast, the transfer of knowledge from master craftsmen to inheritors is a complicated endeavour. For that reason, everyone is facing a great challenge and is exploring the approach in conserving ICH items. Furthermore, the challenge and approach mentioned above only apply to traditional handicrafts. It is hardly possible to verify a particular person as the master craftsman in traditions like Piu Sik which skills are handed down by one person to another. Also, as the Piu Sik Parade is a community initiative, the local government can only encourage the master craftsmen to continue to participate so as to extend the tradition. But what the government may also do is to provide subsidy to the master craftsmen. Nevertheless, as the Piu Sik Parade depends heavily on the initiative of the members of the community, it is inevitable to take its religious implication into account when considering the conservation approach. When drafting the ICH inscription application, the working team was required to include a five-year conservation plan. At that time, the government and the community cooperated to organise a variety of activities, including workshops and guided tours, to promote the Festival. However, since the relevant departments seemed to lack adequate measures to evaluate the activities, there were no follow up actions. Apparently, the government places importance on the development of the traditional culture and heritage of Hong Kong. Some charities such as the Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust does provide financial support while the Hong Kong Tourism Board even promotes the Hong Kong heritage globally. Nevertheless, a refinement in the conservation policy is the most necessary action at the current stage as the Intangible Cultural Heritage Office does not have a formal inspection system on ICH items. For instance, they do not even seek for the submission of a report or to hold a discussion every year. That is to say inadequate tracking mechanism for the conservation and inheritance of ICH items is unavailable. This results in a vacant space to theoretically define the religious rituals of the Cheung Chau Bun and an uncertain direction in terms of conservation of the “Folk Customs” under the national list of ICH. Dr. MA Muk-chi indicated, "The first concern when we talk about the concept of 'inheritance', is to take into account the technicalities in the thinking of the UNESCO and the operational processes in its entirety, as this could lead to a lot of matters being distorted. Then, the second concern returns to the essence of 'inheritance' itself. What does 'inheritance' mean? What does it take to inherit an ICH? The original intention of ICH research was to seek out the endangered heritage. But later on, researchers thought that was not a proper approach. Hence they split the list into two and part of it is what we need to recommend for conservation, covering those ICH items that have been doing well in a cycle and are getting attention, funding and resources. So if the ICH item is doing well, why do you still need to do something about it? Should it not be a normal that you should wish to safeguard ICH items on the edge of extinction? The question is whether the Cheung Chau Piu Sik is going to vanish or not? Even though Cheung Chau Piu Sik did go through some difficult times, the islanders insisted on hosting the parade every year. In the early days, the parade was organised by the community. And today, it remains a 'living', 'organic' cultural artefact as its content and form have evolved. For example, some materials were recycled and reused when resources were scarce, and some teams would tour to other regions for extra income. But, does this constitute a failure to the inheritance of the Piu Sik tradition? Does the effect of the ICH inscription help with the passing on of such cultural tradition? As we are historians, we are conscious of the development of an event, particularly on its causes and consequences. Although Piu Sik is only one part of the Cheung Chau Jiao Festival, the Festival as a whole is the primary concern of everyone. So, you cannot split the Piu Sik Parade apart from the Festival. Moreover, Cheung Chau Piu Sik can now be hired. The Piu Sik one sees in Tai O or Yuen Long are both performed by Cheung Chau people. it is apparent that this phenomenon has become more common after the Cheung Chau Bun Festival got inscribed, and it is commonsensical as the Festival has gained popularity after the inscription and Cheung Chau people are eager to drive tourism with the name of the Festival. In fact, the Hong Kong Tourism Association had chosen the Cheung Chau Bun Festival as the centrepiece of their promotional efforts to attract foreign tourists as early as the 1950s, and the colonial officials had even paid attention to the Festival before the Second World War. Then in the 1960s, the Festival became one of the government’s key projects. All these factors more or less contributed to the development of the Cheung Chau Bun Festival as the colonial government intended to adopt a ‘deliberate interventionist’ policy towards the communities in New Territories after the World War II. These developments are part of history, and they happened long before the inscription application. For that reason, the dilemma about whether to change an ICH is indeed not a concern. In fact, even the UNESCO stated that it is normal for an ICH item to change. And no matter how it has evolved, we should just let it go with the flow as the changes are normal and if people wants to make changes and continue the practice as it changes, then let it be changed. This is the embodiment of the ‘vitality’ of an ICH item. Nowadays, many external factors are attempting to intervene on how ICH items are conserved. The world is not isolated, and as a matter of fact, the inscription system of the UNESCO is already a kind of intervention. The first article of the Convention (or rather, a very important article) stated clearly that the foundational concept of the Convention was conceived after the Second World War. As an immeasurable amount of material cultures was destroyed in the great war, the United Nations figured out a way to come to terms with the loss of these material cultures. This concept, in fact, shares the same root with the concept of the so-called ‘globalisation’ as the UN believed that such culture belongs to the world as a whole in the globe, and the loss of such culture is a loss to the whole world. That's why the UN formulated a set of measures to protect the inscribed ICH items. At the beginning, culture subsisted in the community and was protected by the so-called ‘non-legal restrictions’. But now, international rules require governments to legislate laws to protect culture. Whatever that damages such culture is a criminal office, an illegal activity and is a violation of the laws. Therefore, the use of the laws in protecting cultures connotes that statutes are the only available and valid instrument to define a culture clearly. On that account, how should we define an ICH item? Should we take on the approach that an ICH should be consistent as any changes will cause an ICH item undefinable? But if we accept that ICH items are ‘living’, what kind of changes is considered acceptable? How can one assume that culture has a consistent form when it will not remain constant? But if this is the case, how should we play this game of ICH in the future? If we accept the discourse of ‘cultural vitality’, it is conceivable that the Cheung Chau Piu Sik will evolve without interference. By contrast, if Hong Kong were to adopt the national ICH framework, political ideology may possibly create a more significant impact. For current conservation efforts, it is advisable to understand clearly the history of the ICH so as to recognise as part of the application for inscription that culture changes. As the United Nations Charter also emphasised the vitality of culture, we should retain everything that is in existence and let the society interact with it. For example, the Cheung Chau Bun Festival committee may schedule the Festival on a fixed day, such as on the day of Buddha's Birthday. This is a crucial strategy for the Festival to endure, and it is a decision which the festival committee has to make. Moreover, less intervention on such cultural tradition could enable the community to actively think about what kind of community this should be .As such, instead of directing the development the Festival, the community should decide on its future. Likewise, the community should determine the distinctiveness of their folk religion and influence others with it. This is the sort of approach I adopt. Finally, it is common for one to have a preconception that we are in search of 'what is worthy' when conducting a survey or making choices for an ICH inscription application. However, how does one decide if a matter is worthy? The work for ICH inscription originates out of good faith. In other words, regardless of whether it is the UNESCO or the national ICH office, the belief is that it is striving to preserve something 'worthy'. However, is it obligatory for the matters being preserved and inherited be something 'worthy'? If so, what should we do next? And as a historian, what is my main concern? People in the community who do not understand their heritage thoroughly is my concern. They may neglect the crucial matters as they have to make choices when they lack the relevant knowledge. Hence, being a history scholar, I at least have the responsibility to draw a more complete picture of the activities and the history of the community concerned. Although my comparison may include my judgments on the matters concerned, it will prompt the community to consider this in their own terms and contemplate the change they want. And I believe this is what I am doing.”20 AfterwordIn 2012, the author of this research invited Master AU Lay-kwei from Hing Lung Street Kai Fong Committee to teach the craft of Piu Sik making in class. I then participated in the Piu Sik Parade by coincidence. The Piu Sik parade is a religious ritual that requires a high degree of cooperation among the kai-fongs in the community; it is an embodiment of the totality of the island. As a person who employs art creation as research practice, I regarded the Cheung Chau Piu Sik Parade as an exemplification of Socially Engaged Art; the Parade performance and the underlying craft structure are analogical to the approach of cross-disciplinary collaboration in contemporary visual arts. At the same time, I also realised that only through soundscapes and multimedia can she represent the highly diversified Piu Sik records, documentation, and literature to the fullest. For that reason, the research methods become as well as the research presentation of this research project. During the research, I consolidated photos, manuscripts into experimental and interactive materials. The attempt would not materialise without the collaboration of experts from different fields. Although there is not a definitive conclusion to the questions raised in the research, the respondents from various professions contributed a wide range of profound insights in the different phases of the study. My original research direction was to study the past, present, and future of the Piu Sik Parade. But when I began to study the inheritance and conservation of the parade, the scholarly quality of Dr. MA Muk -chi and his commitment as a historian inspired me to reflect on what me, as an art practitioner, can do to evoke the public to recognise the artistic value of the Piu Sik. Although the public has the choice in respecting the matter they find valuable, I thought that I had at least the responsible for showcasing the issues the people did not notice. Hence, I am eager to present the research outcomes through interactive texts and images, and inform the public the unlearned matters of the Piu Sik. I believed this microscopic presentation approach could minimise the researcher's “interference” to the readers, and hence return the right of cognitive dominance to the community. This idea first came up when I was interacting and interviewing the community members in Cheung Chau. As the community members all showed trust and support to me, I discerned that her relation with them was no longer merely researcher and informants. “This kind of connection, in fact, embodies the down-to-earth sense of community – a relation gradually built up through communication over time. It is a feeling that one would not notice at the very moment. But as the community members unconsciously attend to the details that we concerned with, the community members would begin to notice what is at the centre of attention, and they would be aware of what they are doing.”21 1 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (June 17, 2018). Retrieved from https://ich.unesco.org/en/what-is-intangible-heritage-00003 2 Dr. Wong King-chung (2012) [Grab It] 搶著(pp.50), [General Knowledge on Customs] 風俗通通識. Hong Kong: The Conservancy Association Centre for Heritage. This is the original reference in Chinese. English text quoted from the UNESCO what-is-intangible-heritage-00003 3 Intangible Cultural Heritage Office (June 18, 2018) . Retrieved from what_is_intangible_cultural_heritage.html 4 Ballard, Lina-May. Curating Intangible Cultural Heritage. Anthropological Journal of European Cultures. 17, 1 (Spring 2008):74-95. 5 Lenzerini, Federico (2011). Intangible Cultural Heritage: The Living Culture of Peoples. The European Journal of International Law . 02/2011, Volume 22, pp.101-120. Retrieved from http://www.ejil.org/pdfs/22/1/2127.pdf 6 Arantes, Antonio A. (2007). Diversity, Heritage and Cultural Polities. (24:290). Berkeley, California: Theory Culture Society: Sage Journals. 7 China Intangible Cultural Heritage Network.China Intangible Cultural Heritage Digital Museum (June 18, 2018). Listed under the10th category, “Folk Customs”, in the third batch of the National List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of China. Item number 992 X-85. Retrieved from http://www.ihchina.cn/zhengce_details/11663 8 China Intangible Cultural Heritage Network.China Intangible Cultural Heritage Digital Museum (June 18, 2018). China joined the 2003 Convention and passed the Intangible Cultural Heritage Law of the People's Republic of China in 2004. Retrieved from http://www.ihchina.cn/ 9 Curator CHAU Hing-wah (personal communication, Jan 18, 2019) 10 Curator Chau Hing-wah (personal communication, Aug 16, 2018) 11 Dr. Ma Muk-chi, (personal communication, Jan 28, 2018) 12 Dr. Wong King-chung (2014) Examining the Direction of Preserving Hong Kong’s Intangible Cultural Heritage: A Case of Hong Kong Cheung Chau Bun Festival. A Collection of Speeches and Papers from the Seminars on Hong Kong History. Hong Kong: The Conservancy Association Centre for Heritage. 13 Dr. Wong King-chung (2014) Piu Sik. Passing On: Exhibition of Works by Master Craftsmen and the Apprentices. (pp20-25) .Hong Kong: The Conservancy Association Centre for Heritage. An exhibition with the same title during the same period. 14 Wai Yan Memorial College (2012).非物質文化遺產與身份認同的關係--長洲太平清醮個案歷史追踪 [The Relationship between Intangible Cultural Heritage and Cultural Identity -- Tracking Down the History of Cheung Chau Jiao Festival], Hong Kong: Buddhist Wai Yan Memorial College, Cheung Chau. 15 Cheung Chau Buddhist Wai Yan Memorial College (2007) 探索非物質文化遺產---長洲太平清醮的保育價值及發展 [Exploring Intangible Cultural Heritage -- Conservation Value and Development of Cheung Chau Jiao Festival]. Hong Kong: Buddhist Wai Yan Memorial College. 16 Education Bureau, The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (2014). Case Study of Local Heritage Studies: Cheung Chau Jiao Festival,. Hong Kong Education Bureau. 17 Cheung Chau Jiao Festival Organising Committee(1968). 會景巡遊特刊 [The Carnival Parade Catalogue]. The "Spirit Festival" by Mr W.A. Taylor initially published in the Wide World Magazine. December 1953. 18 Curator Chau Hing-wah (personal communication, Jan 18, 2019) 19 Curator Chau Hing-wah (personal communication, Jan 18, 2019) 20 Dr. Ma Muk-chi, (personal communication, Jan 28, 2019) 21 Dr. Ma Muk-chi, (personal communication, Jan 28, 2019) |