| |

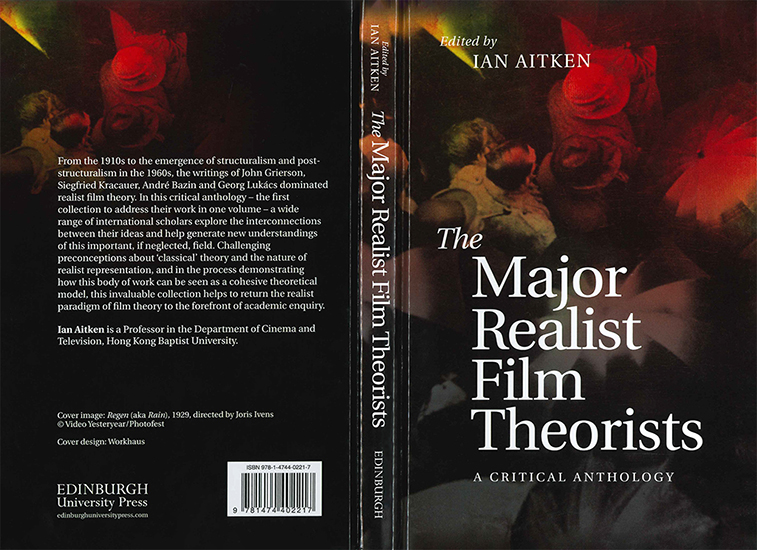

Edited by Ian Aitken From the 1910s to the emergence of structuralism and post-structuralism in the 1960s, the writings of John Grierson, Siegfried Kracauer, André Bazin and Georg Lukács dominated realist film theory. In this critical anthology – the first collection to address their work in one volume – a wide range of international scholars explore the interconnections between their ideas and help generate new understandings of this important, if neglected, field. Challenging preconceptions about ‘classical’ theory and the nature of realist representation, and in the process demonstrating how this body of work can be seen as a cohesive theoretical model, this invaluable collection helps to return the realist paradigm of film theory to the forefront of academic enquiry. Ian Aitken is a Professor in the Department of Cinema and Television, Hong Kong Baptist University.

This book is concerned with the ‘major realist film theorists’. Who may count as a ‘major’ realist film theorist may be open to question, and some theorists may also be considered to be more ‘major’ than others. However, few would disagree that Siegfried Kracauer and André Bazin should be counted as ‘major’ realist film theorists, and, although the names of John Grierson and Georg Lukács may be more contentious, it will be argued here that there are reasons for including the two under this rubric, and for studying the ideas of this group as a whole. One of those reasons, touched on briefly, concerns the shared historical locus and critical providence of these theorists. The publications of the major realist film theorists emerged from the 1910s to the 1960s, that is, from near the beginnings of film theory as such to the emergence of a structuralist, post-structuralist, Screen theory paradigm (‘structuralist’ for short) which dominated film theory from the 1960s until at least the 1980s. The emergence of that paradigm created a divide between itself and what came before, and, in the process, consigned the realist tradition in particular to the periphery of critical concern. As the structuralist paradigm advanced through the 1970s classical realist film theory - and also for that matter realist film practice – additionally became regarded not only as extraneous but also problematic because (a) the emphasis on understanding and portraying the relationship between film and the experience of perceptual reality within that theory and practice meant that the foregrounding of signifying practice in film – a prerequisite of the newly-dominant paradigm - was not given priority; (b) the epochal-humanist orientation of classical realist film theory was seen to be at odds with the politics of more historically-specific class, race and gender activist intervention which became a preoccupation of post-classical realist film theory; and (c) the classical-realist stance was seen to contribute in part towards the ongoing and escalating naturalisation of the status quo so that what was required was an ‘anti-realist’ film theory and practice which would deconstruct and undermine such naturalisation - and whilst the preoccupation with postmodern film theory and practice from the early 1980s onwards led away from such political-modernist deconstruction that preoccupation only served to further sideline the classical-realist tradition. As the authors of one illustrative publication put it, ‘film theory gradually transformed itself from a meditation on the film object as the reproduction of pro-filmic phenomena into a critique of the very idea of mimetic reproduction’ (Stam and Flitterman-Lewis 1992: 184). Nevertheless, at least one of the major realist theorists, Siegfried Kracauer, became an increasing focus of critical attention from the early 1990s onward, though most of the attention paid to Kracauer focused on the accounts of modernity found in his early Weimar writings rather than the coverage of realism found in his 1960 book on cinematic realism, Theory of Film; and it has even been argued that an ‘epistemological shift’ can be detected between the superior ‘early’ Kracauer and poorer ‘late’ ‘realist’ Kracauer (Petro, in Ginsberg and Thompson 1996: 97). In contrast to Kracauer the theories of the remaining major realist film theorists, Grierson, Bazin and Lukács, have been more neglected. It has been attested that Bazin suffered the most here and that ‘Since the 1960s we have gone through a period in which Bazin bashing has become fashionable in film-theoretical discussion’ (Rosen in Margulies (ed.) 2003: 42) Whether Bazin has been ‘bashed’ more than has Grierson or Lukács is, however, a moot point. Some recent books on Bazin have appeared which seek to counteract such bashing, including Margulies (ed.) (2003), Rites of Realism: Essays on Corporeal Cinema, and Andrew and Joubert-Laurencin (eds) (2011), Opening Bazin: Post-War Film Theory and its Afterlife; and it seems that the re-evaluation of Bazin will continue, hopefully spurred by the essays on Bazin in this anthology. The two least tackled figures are Grierson and Lukács, and that is partly because they are connected to a Hegelian tradition of thought that is little accommodated within contemporary English-language film studies. Grierson continues to be a focus of attention on account of the role he played within the development of the documentary film in Britain and elsewhere, and, against a background of growing interest in the colonial official film, a number of reassessments of Grierson are currently underway. Whilst, however, it has been established since at least the 1970s that Grierson’s approach to the documentary film sprang from neo-Hegelian sources there seems to be little ongoing interest in Grierson’s intellectual theory of film per se, though this is covered in Hillier and Lovell (1972), Aitken (1989, 1990, 1998, 2001, 2006, 2007, 2013) and Ellis (1968, 1973, 2000). Of course, Grierson’s reputation as somebody who promoted a limited-reformist rather than radical vision of the documentary film has also contributed to this lack of interest, and even antipathy, with one critic writing in 1983 going as far as to assert that ‘the basic thing is to break open the “prison” of Griersonism’ (Lovell, in Macpherson, D (ed.), 1980: 18). As with Grierson, so with Lukács, though the latter is arguably perceived to be more problematic than the former: Grierson may have been a ‘conservative’ but Lukács, some claim, was a ‘Stalinist’. Lukács’ theory of aesthetic realism has also been the subject of criticism, and one of the most scathing of such is that his model of literary realism dismissed some of the most vital artistic movements of the nineteenth and twentieth-centuries. Lukács’ disavowal of naturalism proved relatively uncontroversial given the extent to which the naturalist tradition had fallen out of favour by as early as the late-1940s. However, his rejection of modernism brought his theory of realism into disfavour against a context in which modernism was widely regarded as a progressive form of artistic intervention. Nevertheless, an analysis of Lukács’ early and late writing on film reveals them to be compatible with both naturalism and modernism. For example, in the early ‘Thoughts Towards an Aesthetic of the Cinema’ (1913) Lukács celebrated the modernist possibilities of film; whilst, in the The Specificity of the Aesthetic (1963) he developed an impressionist-naturalist theory of film (Aitken 2012). In addition to the charge of anti-modernist bias, a second accusation levelled against Lukács concerned his alleged association with Stalinism and Soviet totalitarianism. This accusation, summed up in Lezlek Kolakowski’s assertion that Lukács helped forge ‘the conceptual instruments of cultural despotism’, has been reiterated by many commentators from the 1930s onwards (Kolakowski 1978: 305). However, in fact, Lukács’ relationship to the Soviet dictatorship was ambivalent. When the Hungarian Revolution broke out on 23 October 1956 Lukács was made Minister of Culture. However, after the Soviet invasion of 4 November he was deported, narrowly escaping execution, and expelled from the Communist Party. Between 1957, when he was allowed to return to Budapest at the age of seventy-two, and his death in 1971, Lukács played only a minor role in high political affairs, though he continued to agitate for political reform. Throughout the bulk of his career, therefore, Lukács championed positions to the liberal-left of official Party policy, and, though a committed Leninist was also a staunch opponent of Stalinism.

The writings on film of the major realist film theorists span a period from the 1910s to the 1960s. Probably the earliest published contribution came in 1913, and from Georg Lukács. His ‘Thoughts Towards an Aesthetic of the Cinema’ appeared in the German newspaper Frankfurter Zeitung und Handelsblatt that year as a contribution to the ongoing debate about the cinema known as the ‘Kino debate’. The article, Written in German, has been translated into English several times. Lukács also wrote a number of essays on film translated into Italian in the Italian Marxist film journal Cinema Nuovo in the 1950s and 1960s. Finally his chapter on film in his The Specificity of the Aesthetic (1963) was translated into English for the first time in 2012 (Aitken). In addition to these writings on the cinema though, it is not really possible to ignore Lukács’ writings on literature when considering him as a major realist film theorist because those writings contain ideas that reappear in and or contradict the writings on film. John Grierson began writing on film in 1925, initially on issues related to how the Hollywood film might accommodate a social-realist dimension. Grierson’s early model of ‘epic cinema’ was based on such a premise. However, when he realised that Hollywood was beyond such reform Grierson turned to the documentary film. His first written piece on the documentary film, ‘Notes for English Producers’, appeared in 1927, and remains unpublished to this day. This is surprising given that it proved to be the founding document of the documentary film movement. ‘Notes for English Producers’, a memorandum written for Grierson’s then employer, the Empire Marketing Board, set out the model of documentary film which was eventually realised in the shape of his 1929 film Drifters. Between 1929 and 1939 Grierson wrote on the cinema and documentary film and these writings have appeared in a number of outputs, most notably Grierson on Documentary (F. Forsyth Hardy (ed.) 1946). The influence of philosophical idealism on Grierson appears across these writings to one extent or another. However, that influence also appears in unpublished essays that Grierson wrote whilst at university. The ideas expressed in these published and unpublished writings covering a period from 1919 to 1939 include the key works written by Grierson. After 1939 his writings become less significant at a theoretical level, and what happened here is that an early concern with philosophical aesthetics was superseded by a less sophisticated discourse on propaganda, corporate public relations and instrumental ‘civic education’ (Aitken 1988: 41). Grierson remained based in the United Kingdom for most of his career, with some relatively-brief periods spent in Canada, and in travelling from place to place. Lukács also remained mainly in Hungary, though often under condition of restraint. The career of Siegfried Kracauer was, however, divided into two parts. The first phase of Kracauer’s career was spent in Germany, and his German writings appeared between 1923 and 1930. In 1925 Kracauer published an essay entitled The Detective Novel, on aspects of everyday life in the modern German society surrounding him. After that he continued to write on aspects of contemporary mass culture, and essays on this were published in 1927 as The Mass Ornament. Finally, in 1930, he published The Salaried Masses, on the growth of the white-collar employee class in Germany. The majority of this work had little to do with film, though. In 1933 Kracauer left Germany in order to escape the rise of Nazism. He then stayed in France until 1941, after which he left for the United States. In 1947 he published his first full work on film, From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film, and then, in 1960, Theory of Film: the Redemption of Physical Reality. Kracauer died in 1966, and his final work, on history, rather than film, was published posthumously in 1969. In contrast to the much-travelled Grierson, Lukács and Kracauer, all of whom were strongly influenced by German classical philosophy, the final major realist film theorist, André Bazin, remained firmly at home in France, and was mainly influenced by the French intellectual tradition, though the influence of phenomenology also links him to the other three. Bazin began writing film criticism in 1943 and co-founded the film journal Cahiers du Cinéma in 1951, writing in this journal and elsewhere until his death in 1958 at the age of 40. Virtually all of his writings were, therefore, essays in film criticism which appeared between 1943 and 1958, and, after his death, these were republished in various anthologies, beginning with the four-volume Qúest-ce que le cinema? (1962), and followed by a two-volume selection and English translation of this in 1967-71. After this the following appeared, compiled by a variety of editors: Jean Renoir (1973), Orson Welles: A Critical View (1978), French Cinema of the Occupation and Resistance: The Birth of a Critical Aesthetic (1981), The Cinema of Cruelty: From Buñuel to Hitchcock (1982), Le Cinéma Français de la Liberation à la Nouvelle Vague (1983), Essays on Chaplin (1985), Bazin at Work: Major Essays from the Forties and Fifties (1996) and André Bazin and Italian Neorealism (2011).

One of the objectives of this Introduction is to establish the core conceptual framework underlying the thought of the major realist film theorists. Before attempting that, it may be helpful to set out an understanding of what might be meant by the term ‘realism’ more generally. There is, admittedly, no need per se to engage in such an undertaking, as it would suffice to provide an exposition on the core conceptual framework just referred to. On the other hand we are, as the term indicates, dealing with supposedly realist film theory here, and, given that, there is some obligation to address and also a challenge to confront the issue of what that term might mean in general, as well as in relation to film. The term ‘realist’ in ‘realist film theory’ implies an attempt on the part of the theorist to establish a link between film and ‘reality’. However, and as mentioned, the supposition of such a link has also been responsible for the derogation of realist film theory and the major realist film theorists, because the aggregation of the two terms ‘represent’ and ‘reality’ is seen to imply both a belief in objectivism and the idea that reality is in some sense ‘unitary’; and both premises are at odds with contemporary commendation – within film studies - of a stance founded on pluralism and difference. It is also argued, as mentioned, that the quest to establish such a link between film and ‘reality’ may play an albeit unintended part in the legitimation of dominant discourses concerning what is and is not warranted, true and real; because a prevailing hierarchical order will always seek to tie essentialism of different sorts, including that related to film, to its own expediency. Here, the notion is that the supposed essentialist tendency within realist film theory accrues to and reinforces on-going general processes of hierarchical naturalisation by implication. This is one reason amongst others why some recent writing on cinematic realism has tended to focus on the conventionalist characteristics of realist techniques and avoid such essentialism; and this has become something of a paradigm limit-wall. For example, one writer attempts to study the ‘reality effect’ of film, and also relates the concept of realism to notions of vital affect, strong feeling, realistic-ness, and so on: in other words to conventionalist and culturally-established relations (Pomerance 2013: 3-5). Another asserts that the aim is to: analyse some of the ways in which realism is experienced….not aim to provide a definition of what is real, but to describe and characterise some of the different processes and elements that cause viewers of audiovisual representations to have an experience of ‘realism’ (Grodal in Jerslev 2002: 67) Other examples could be given of this attempt to understand realism in terms of technique, convention and expectation. This is of course a perfectly valid and sensible way to approach the issue. However, it does not and should not rule out other approaches, and the importance and magnitude of the question of realism has therefore led to the recent appearance of work which seeks to probe the issue from a variety of angles, and uncertainties, including Margulies (2003), Nagib (2011), Nagib and Mello (2009), Hallam and Marshment (2000), and Rushton (2011). The term ‘probe’ used here is also notable, because it seems that the elusive question of realism can only be probed rather than ‘faced’; can only be engaged and disengaged with in a series of critical on-going, cautious encounters. Thus, the various contributors to this book also approach the question of classical cinematic realism in different ways in order to open up the subject further; whilst the ambitious project of this Introduction is to construct a reconsidered model of what I will call ‘phenomenalist realism’, explore key concepts from continental philosophy in some depth, and also relate these to the analytical tradition in philosophy. This Introduction is therefore speculative and explorativein character, and aims to probe the issue of realism from a number of perspectives in order to suggest new ways of considering classical realist film theory, and encourage new pathways of research into the subject. Classical realist film theory is a form of realist film theory. However, the latter still comprises only a small part of a substantive body of theory which addresses the major issue of realism, and, in order to place classical/realist film theory within that larger body it will be helpful to outline the principal representational models that comprise it. This will require a brief excursion into the field of analytical philosophy. 1 Realism need not imply simple objectivism. Theories of realism which imply such replication are sometimes referred to as theories of ‘direct’ realism because in them representation is seen to correspond directlyto reality. However, though such direct or ‘naïve-realist’ theories of representation have a considerable historical lineage they are difficult to support at a theoretical level and few contemporary theorists subscribe to them. In contrast to direct realism, ‘representational realism’ is premised on the conviction that, although external reality exists independently of our representations of it, it cannot be known independently of such representations. However, although representations are our own constructions, representational realism contends that they have some sort of relationship to reality and are able to indirectly represent reality (Hesse, in Morick (ed.), 1980: 198). However, the indirect character of representation proposed by representational realism also carries within it the potential for a relativist locus based on the idea that we might in fact only have knowledge of representational systems and have no way of knowing whether or not those systems have any link to ‘reality’. Such a position implies and may also lead to extreme forms of ‘ontological idealism’ and solipsism, as is, for example, implicit in Bishop Berkeley’s postulate that the world may be an ‘emanation of the ego’ (Russell 1965: 20). Like direct realism, such ontological idealism is also difficult to maintain though, because it leads to the proposition that mind is the only reality, and that reality is the creation of mind, and, since Berkeley, ‘most philosophy’ has sought to distance itself from such a position, which is considered ‘inimical to social sanity’ (20). Ontological idealism is, therefore, not only contrary to realism but also precluded by most so-called ‘anti-realist’ philosophies, including ‘conceptual idealist’ ones. Conceptual idealism is probably the most common anti-realist or non-realist philosophical position today. Conceptual idealism picks up on the palpable flaw in any realist position: that if representation does converge with reality such convergence cannot be easily or at all demonstrated; and asserts that, although ‘reality’ may exist in some sense, we can have little or no knowledge of it per se and only have knowledge of our concepts, consciousness and representations of it. There is, for us, no ‘reality itself (whatever that might be) but reality-as-we-picture-it . . . reality-as-we-think-it = our reality, is the only reality we can deal with’ (Rescher 1973: 167). Conceptual idealists do not adopt the ontological idealist position that reality is the product of mind but instead argue that the main task of the theorist is to understand how our conceptual schemes construct meaning for us. This also implies that attempts to theorise the link between representation and reality will largely be a waste of time and effort. This conceptual idealist account of representation also implies a relational and conventionalist rather than correspondence model of knowledge in which it is thought better to assess a representation in terms of its relationshipto other representations within a conceptual scheme than in terms of any correspondence to ‘reality’. Such a theory of meaning can also become formalised around terms and relations internal to a conceptual scheme, and to the exclusion of external reference, as, for example, is the case with some semiotic and structuralist theories. At one level, it could be argued that no fundamental distinction exists between representational realism and conceptual idealism, that the difference between the two is one of degree, that there are therefore similarities between the two, and that both can be categorically separated from the twin extremes of ontological idealism and naïve realism. However, whilst accepting that, there also remain significant differences between representational realism and conceptual idealism, and these also have a bearing on realist film theory. In terms of similarity, both representational realism and conceptual idealism stress that the world exists (both are therefore forms of ontological realism), but cannot be considered independently of any particular representation of it, and that, therefore, a completely concept-independent reality cannot be meaningfully experienced or theorised (Putnam 1987: 27). However, representational realism differs from conceptual idealism in stressing that correspondence between reality and representation can be justifiably theorised to an extent and should be so theorised. Realist theory, whether related to philosophy or film, is ineluctably connected to a sense of vocationto develop a model which can account for the relationship between representation and reality. Representational realists believe in the need to account for this, even though no ‘objective’ account can ever be elaborated. This is what is meant by the phrase ‘realism of intent’, which will be discussed shortly in relation to the ideas of the philosopher Hillary Putnam. Realism, like other abstract universals, is, therefore, a calling for some, and, within philosophy, one such model which has answered that call, and which will be outlined here by way of example before returning to issues related to realism and film, is Putnam’s theory of ‘internal realism’. ‘Internal’ realism is so called because, as Putnam argues, any representation of reality must be formulated within a particular conceptual scheme and cannot transcend such a scheme in order to face external reality per se, even though – Putnam contends - such a reality must be presumed to exist (Putnam 1981: 52). This premise, as has already been argued, is central to any representational-realist position, and differentiates such a position from naïve realism and ontological idealism. However, and crucially for Putnam, this position also means that fundamental dichotomies between inside and outside: between subjectivity and objectivity, convention and fact, reality and representation, truth and falsity, must be eradicated, because what Putnam refers to as the ‘cut’ between inside and outside cannot be made: The attempt to draw this distinction, to make this cut, has been a total failure. The time has come to try the methodological hypothesis that no such act can be made’ (Putnam 1987: 27). If it is accepted that external reality exists yet cannot be grasped directly objectivism and subjectivism are insufficient and a middle-ground between both must be established. Such a position actually has greater implications for conceptual idealism than representational realism, because, whilst representational realism encompasses both inside and outside, conceptual idealism effectively brackets outthe outside on the grounds that it is not worth considering in that, although it exists, it cannot be comprehended. This is, in Putnam’s terminology, and to all extents and purposes, a ‘cut’ between inside and outside to the detriment of outside; and, if conceptual idealism believes in the existence of a reality outside of mind it is a cut that should not be made. If, though, reality is brought back into the equation in some way, then the conceptual-idealist stance (including its related politics) is brought into question. In place of such a cut Putnam proposes a suture of inside and outside that accommodates the middle-ground of each as he adopts a model based on a continuum of the ‘relatively subjective’ and the ‘relatively objective’ (or relatively inside-relatively outside) (29). Putnam’s model of internal realism rules out ontological idealism and naïve realism, and, as argued, also undermines aspects of conceptual idealism. However, what are still required are methods and procedures for knowing something ‘relatively objectively. If the ‘cut’ cannot be made, what means and approaches can accomplish such approximation? As a philosopher in the analytic tradition Putnam is concerned to elaborate conceptual means to this end and so has developed a model based upon the privileged status of rational procedures - what he refers to as ‘canons and principles of rationality’ and ‘warranted assertability’ criteria; which set limits upon the remit, acceptability and array of interpretation (34). These canons, principles and criteria interact with experience to create an ‘explanation space’, a circumscribed area within which certain accounts of reality can be argued to be more justified than others because they are ‘instrumentally efficacious, coherent, comprehensive and functionally simple’ (Putnam, in Passmore 1991: 106). What we have here, therefore, is what amounts to a ‘regulative conception’ of realism: a ‘realism of intent’, rather than ‘definitive truth’, delimited by conceptual principles (Rescher, in Trigg 1989: 201-2). It will be argued here that Putnam’s notions of the ‘relatively subjective, ‘relatively objective’ ‘warranted assertability’, ‘canons and principles of rationality’ and the idea, from other sources, of a ‘realism of intent’, go part way to establishing an adequate-enough basis for a representational-realist position; that is, they provide part of an intellectual justification for realism and rebuttal of the core premise of conceptual idealism. Realism is necessary because the ‘cut’ between inside and outside cannot be made, because the outside exists, and because the inside can (perhaps must) strive to become proximate with the outside. Realism involves a pursuit of this approximation and is a ‘realism of intent’ as a consequence. Warranted assertability criteria and canons of rationality do not, of course, have much bearing on the ideas of the major realist film theorists, most of whom seek to limit rather than lionise rationality. However, and as will be argued later, the notions of a ‘realism pf intent’ and desire to retrieve the ‘outside’ have considerable resonance with those theorists. In addition to these ideas derived from Putnam and others, though, there is one final area of philosophical enquiry which must be considered before turning to realist film theory, and one also which adds an additional dimension to the overall justification of realism attempted here. Conceptual guidelines may help in achieving ‘convergence’ between inside and outside, but so might empirical experience, an area crucial to the major realist film theorists and any realist film theory. Many philosophical realists believe that perceptual experience constitutes our most dependable though still circumlocutory relation to a reality which exists outside our conceptual schemes. Within such experience, our perceptual apparatus constructs a phenomenal world which surrounds us. However, our perceptual apparatus constructs that world in relation to something, and that something can only be something outside of our conceptual schemes which is influencing how our perceptual apparatus is constructing perceptual experience for us. Unless one takes the view that our perceptual apparatus constructs appearance in relation to the internal functioning of the apparatus this has to be the case. So, there is a reputed link between perceptual experience and independent, unobservable causal factors, and because of this perceptual experience must be a, or even the starting pointfor understanding or appreciating those factors. It is because unobservable causal factors are unobservable, and also because the phenomenal world is observable, and is also linked to those factors, that perceptual, empirical experience has for many theorists a special status in relation to the question of reality (Devitt 1997: 108). One formulation which also relates to this and is relevant here is that of ‘empirical adequacy’. Here, for a representational scheme – for present purposes a theory about something - to possess empirical adequacy, it must engage with a substantial quantity and diversity of perceptual phenomena (Trigg 1989: xiv). Such a degree of engagement is beneficial because such phenomena are linked to external reality, and because phenomenal experience generate a more extensive and nebulous quantity and diversity of connotations and relations than concepts, which are fashioned and limited by their determinate conceptual nature (Hesse, in Morick 1980: 217). So, there are two issues here: the link which phenomenal representations have to external reality, and their ability to qualify theoretical supposition. These issues also really relate here to the notion of evidence: evidence that is used to sustain or negate a theoretical formulation; and this is because the notion of empirical adequacy is derived from the philosophy of science and is chiefly concerned with issues of theory verification and refutation. However, if, in place of a theory, a representational system is considered in relation to the notion of ‘empirical adequacy’ the following emerges. For a representational system – say a film - to possess empirical adequacy that system should engage with a substantial quantity and diversity of empirical phenomenal materials. The presence of a surfeit of empirical phenomenal materials in the representational system (film) will enhance and enrich the array of signification and problematics present. In addition, if the representational system is a film which contains albeit cinematically-coded representations of perceptual experience, given that, as previously argued, there is a link between perceptual experience and independent, unobservable causal factors in reality, there will also be a link between the coded representations of perceptual experience in the film and factors existing in reality; and this also means that the more such coded representations of perceptual experience constitute the film the closer and greater that link will be, at least on the basis of quantity: these representations therefore have a mass which bears down upon the unobservable. Such hypothetical approximation can, of course, never be verified, in the commonly-accepted sense of that term, but works rather in the way of a guideline, and as a ‘realism of intent’. Of course, as an aesthetic structure, the film will contain other sorts of coded structural and conceptual components. However, according to the tenor of the above, coded representations of perceptual experience should predominate. As will be argued later, the notions referred to above have implications for understanding the ideas of the major realist film theorists. Before turning to these, though, it will be useful to return to Putnam’s model of internal realism in order to discuss an aspect of his thought which is congruent with those ideas. Putnam has argued that his model was formed partly in response to a scientific world view which had ‘turned the external world’ into ‘mathematical formulas’, therefore making our own experience of the world a ‘second-class’ one (Conant, in Putnam 1992: xiv). Putnam claims that he wishes to resist this and confront the hegemony of the scientific world view by raising up such experience, and, in doing so, he invokes the idea of the Lebenswelt, or ‘life-world’: I am concerned with bringing us back to precisely these claims which we do, after all, constantly make in our daily lives. Accepting the ‘manifest image’, the Lebenswelt, the world as we actually experience it (xlix-l). The trajectory of Putnam’s thinking thereby leads him to a conception of realism which embraces the ‘manifest image’ of the Lebenswelt: that which is phenomenally felt; and his notions of ‘realism with a human face’ and ‘realism with a small r’ also reflect this concern to comprehend ‘ourselves-in-the-world’ (xiv). The idea of turning towards everyday experience within the Lebenswelt and concomitantly limiting the latitude of conceptual rationalisation is of course central to the ideas of the major realist film theorists, particularly Lukács and Kracauer; and, it could be argued, underlies the whole of Kracauer’s Theory of Film. Putnam’s emphasis upon the notion of what he also calls ‘human flourishing’ also brings him in line with the humanist orientation of Kracauer, Bazin and Lukács, and there is a particular resonance, for example, between the notion of ‘human flourishing’ (xv) and Kracauer’s idea of the ‘family of man’ (ref). Nevertheless, whilst these aspects of Putnam’s thought may correlate with the ideas of the major realist film theorists his focus on conceptual categories such as ‘canons and principles of rationality’ does not because film, for the realist film theorists, is an aesthetic rather than rational-cognate form of representation. There is, therefore, a need to understand how the sort of realism discussed in the previous pages might be framed in aesthetic terms.

One starting point here is the notion of empirical adequacy and the idea of phenomenally-laden realism. However, the notion of empirical phenomenal adequacy also suggests that the empirically-laden aesthetic object will also be indeterminate because what is largely empirical is also necessarily largely indeterminate. Aesthetic objects, including films, may, of course, not be empirically-laden, and may also vary in indeterminacy in terms of their aesthetic structures. However, it has been argued that the process of encountering an aesthetic object – aesthetic experience - is in general marked by indeterminacy. So, for example, it is argued that works of art are rarely judged to make truth claims about a subject because people do not come to the work of art to find specific answers, as perhaps they might to a cognitive tract like a cookery manual, or an instructional film. The ‘knowledge’ which is generated during aesthetic experience is not veridical cognisable knowledge. Rather, the spectator is on the lookout for something that might be ‘intellectually illuminating’ in a broad sense rather than cognitively definite (Passmore 1991: 125). Instead of making truth claims works of art ‘offer a subject’ up for scrutiny or ‘show something as’ similar to that which the spectator might experience or believe (Beardsley 1981: 375). Here, the work of art shows something as like something in a general rather than specific way; it ‘draws attention to’ a subject, or puts a subject ‘up for consideration’, instead of making more precise claims; and It does not thereby display truth so much as ‘interesting candidates for truth’ which the recipient can then consider (Passmore 1991: 125). Within this process the role of the formal organisation and ideational content of the work of art is also regarded by the recipient as providing a broad rather than narrow perspective on the subject (138). Of course, these are generalisations, and some works of art may be more purposely directive and received as such than others. However, the point here is that, in general, works of art are not generally taken to provide definite truth claims, and even the most highly-composed works of art may be interpreted, or experienced, in a largely indeterminate fashion. This adds an extra dimension of indeterminacy to the already indeterminate phenomenally-laden aesthetic form indicated previously, and may suggest that such a form might be more appropriate to aesthetic experience than one which is not so phenomenally abundant. The indeterminacy referred to above is also predicated upon the concept of intuition, which is a key aspect of classical realist film theory. It has been argued that three main categorical epistemologies of knowledge can be posited: empiricist, rationalist and intuitionist (Beardsley 1981: 387). Within an empiricist epistemology all knowledge stems from experience and can only be understood through a process of rational generalisation from perceived instances. In contrast, within a rationalist epistemology, it is held that real knowledge may be given independently of experience and may also subsist within some ideal realm separate from the world of nature, accessible through reason. However, classical realist film theory cannot be associated with either of these positions. For example, despite the emphasis upon the empirical which underlies such theory that theory cannot be said to rely upon an empiricist theory of knowledge, in that neither Lukács, Grierson, Bazin nor Kracauer adopt the view that all knowledge stems from experience, and can only be understood through a process of inference from experience. Similarly, none of the above theorists accept the alternative rationalist proposition that real knowledge may be appropriated independently of experience or that it may subsist within some ideal realm accessible through reason. Instead, classical realist film theory is most closely aligned with the third major categorical epistemology of knowledge, ‘intuitionism’. The first thing to be said about intuitionism as a theory of knowledge is that it is not a theory of knowledge in the typical sense understood by that phrase because it does not seek to provide a rationale for ‘proving’ anything and so does not involve the making of specific truth claims about anything. This effectively means that there is no actual obtained knowledge involved here if knowledge is understood as something demarcated and delimited: something that can be definitely known and also something that can be clearly communicated to others. In contrast to that, an intuitionist theory of knowledge is concerned with indefinite knowledge that is also comprehended ‘intuitively’: with an equivocal awareness of something ambiguous but resonant ‘grasped’ or ‘felt’. In addition to such indeterminacy, intuitive understanding cannot really be communicated in its essence because it is something experienced in the moment by the individual person who experiences the intuition. Intuitionist understanding is, therefore, related to personal revelation, though, because human beings live a shared existence it also has a collective and communicable – but, as stated, not essentially so - dimension. In this sense, intuition, though primarily subjective, is also secondarily inter-subjective. Whether subjective or intersubjective, though, intuitive awareness cannot be anchored and set down for scrutiny because it is momentary and transient and appears and disappears in a process of transient flux and change. No painting, for example, can ‘capture’ an intuitive insight, though it may be the product of such insight and may act as a catalyst for spectatorial insight that may or may not be similar to the original insight. Finally, in addition to the above, Intuitive understanding is also conjectural and hypothetical in character rather than conclusive and summative. It is not concerned with solutions either elementary or elaborate. Two consequences stem from the above which have ramifications for an understanding of intuitionism in general and classical realist film theory in particular. First, and in terms of experience, the conjectural, hypothetical and transient character of the form of knowledge proposed within an intuitionist theory of knowledge implies that there will be no definite bracketing in or out or categorising taking place within the formation of such knowledge, and this means that intuitively-provoked knowledge will not be complicit with proclivities towards jurisdiction, regulation and the imposition of authority. In other words, intuitive understanding stands outside and is foreign to processes of authorisation and is associated instead with the antithesis of such processes, that is, non-discriminatory disinterestedness. Second, and in terms of aesthetic representation, because intuitive understanding is related to feeling rather than intellect, to mood rather than concept, it is best or can only be portrayed through non-verbal non-conceptual forms of art; and this also means that such forms of art can also, in principle at least, be similarly related to notions of non-discriminatory disinterestedness. These issues of freedom, control, and the importance of non-verbal modes of representation, will be returned to later as they are central to classical realist film theory. Before that, however, it will be necessary to focus further on issues of ‘reality’ and representation within intuitionist theories of knowledge. Intuitionist theories of knowledge, under which rubric classical realist film theory falls, are experience-oriented in the sense that the reality in question is understood as or limited to that which is experienced. To one extent or other this focus on experience can also be related to or even be directly influenced by the phenomenological notion of the Lebenswelt: the surrounding ever-changing world of our everyday experience and perception. As we have seen, this notion is referred to by Putnam, but other philosophers in the analytical tradition have also made reference to the notion or similar. For example, john Dewey has argued (without mentioning the term Lebenswelt) that human experience is marked by a fluid continuum that is essentially inchoate and unstructured. A particular experience may have definite parameters but is also extracted out from the more extensive parameter-less inchoate flow of overall experience (Hanfling 1994: 151). This conception of human experience as characterised by flux has a lineage within Western philosophy and emphasises becoming rather than being, process rather than conclusion, change rather than stasis; and is summed up in a phrase attributed to the Greek philosopher Heraclitus: ‘nothing ever is, everything is becoming’ (Russell 1965: 63). This notion of becoming was later taken up by Hegel, Nietzsche and others and went on to influence classical realist film theory. An intuitionist theory of knowledge may also define intuitive understanding at two different levels of consequence. First, there is the general intuition of something meaningful. This can be of almost anything in terms of what is experienced, but is nevertheless always characterised by a similar type of process: an intuitive grasp of resonant meaningfulness through feeling and personal encounter. Intuition is not generated unless the object of intuition is worth intuiting. The traveller stands in front of the mountain and experiences its magnificence, or terror, and it is personal experience of aspects of the life-world such as this that generates this type of intuitive experience. If the viewer looks at a painting of a mountain the same type of experience may be generated, though that experience may also be different from ones experienced by the painter, as she attempted to embody those experiences in the painting (though the painted mountain may also be entirely the product of the artist’s imagination, and not based on her personal experience of a mountain). In addition to these kinds of intuitive understandings though, there can also be a more particular intuitive awareness of the authentic quotidian character of experience of the Lebenswelt, of the phenomenal world, and this can also be accompanied by insight into what a superior comportment of the individual within the Lebenswelt might consist of. This now takes us back to the idea of empirical adequacy, and to the notion that, if our perceptual representations are linked indirectly to an external world which exists outside of our conceptual schemes, then empirical adequacy based on and in perceptual representation in aesthetic representation also links us to that world and to a kind of experience of knowing that world. Nothing mystical is involved here, and what is being referred to is a concrete sense of being in the world: a sense of grasping the authentic – and therefore realistic - character of our place within a Lebenswelt which is also ineluctably linked to external reality. Here, empirical adequacy in the film connects us to this deeper level of experience of insightful experience of our existential situation. This idea is also taken up by Dewey (though, of course, not in relation to film), and also related to the notion of becoming, when he asserts that: life goes on within an environment…we continually interact with our surroundings, seeking an enrichment, stability and harmony with them…a fulfilment that reaches to the depth of our being – one that is an adjustment of our whole being with the conditions of existence (Dewey, in Hanfling 1994: 151).Dewey’s expressive language: ‘a fulfilment that reaches to the depth of our being…an adjustment of our whole being with the conditions of existence’ sums up the importance of this notion not only for him but also, and as will be argued shortly, for the major realist film theorists, whose underlying ideas embody similar sentiments concerning the revelation of the individual’s relation to the Lebenswelt, the world of phenomenal experience, and, through various representational formulations of empirical adequacy (though that phrase is not used by them), to external reality. Before considering those underlying ideas, though, one important misconception must be confronted concerning intuitionist theories of knowledge, and that is that they may constitute some sort of romantic numinous repudiation of intellect. In fact, this is rarely the case, and most intuitionist theories of knowledge do not repudiate intellect per se but rather seek to position it better within the totality of human experience. Intuitionist theories of knowledge, including classical realist film theory, generally seek to argue that intellect and rationality have become too dominant within modern human experience at the expense of other important areas, and must now be placed within a more appropriate perspective, one which also recognises the importance – perhaps over-riding - of intuitive experience.

The preceding section of this Introduction has set out an overall framework of aesthetic realism related to classical cinematic realism and premised on notions of phenomenal adequacy, the indeterminate character of aesthetic experience and the nature of aesthetic intuition. The objective will be to eventually use this framework as a basis for understanding the general and to some extent collective theoretical position of the major realist film theorists more clearly. This section of the Introduction will therefore proceed to that end by first prefacing the intuitionist aspect of classical realist film theory - in order to link up with the previous account of aesthetic intuition - before going into more detail on a general categorical feature of that theory, and perhaps the one that will best enable an overarching understanding of classical cinematic realism to be reached: the focus on particularity. However, the many specific ideas and concepts found in the writings of these theorists will only be considered briefly and in part in the preface on intuitionism set out here, and will not be considered extensively in the larger section on particularity. This is because that would be unachievable given the space remaining here and has anyway been carried out reasonably exhaustively elsewhere (including Aitken 2001, 2006, 2007, 2012 and 2013); and because the intention here is to arrive at an understanding of the general classical cinematic realist category of particularity through relating that category to other general theoretical formulations which influenced it rather than instances which comprise it.

The outline of classical realist film theory carried out in the following few pages reveals that such theory is demonstrably part of the larger intuitionist paradigm indicated in previous pages. Lukács’ early and late writings on film are full of intuitionist notions. For example, in his 1913 ‘Thoughts Towards an Aesthetic of the Cinema’, he writes that: The world of the “cinema” is a life without background or perspective, without distinction in terms of weight and qualities…a life without measure or order…the essence of cinema is movement as such, perpetual flux, the never-resting change of things (Lukács, in Aitken 2012: 182-3). Lukács’ early work was strongly influenced by phenomenology and the notion of the Lebenswelt underlies the 1913 essay. Similarly in the chapter on ‘Film’ in the 1963 Specificity of the Aesthetic Lukács makes distinctions between what he calls ‘indefinite objectivity’, ‘definite objectivity’, and ‘interiority’. Art forms such as literature are able to portray interior subjective experience well because they employ conceptualisation. However, visual and auditory art forms such as film are only able to depict interiority indirectly: to indicate, rather than conceptualise; and this process of the indirect non-conceptual depiction of interiority is what Lukács refers to as ‘indefinite objectivity’. Lukács also argues that, because film is a primarily visual medium, within which language plays only a secondary role, it must prioritise the ‘visual-auditory’, or ‘sensuous-immediate’ - rather than conceptual (Aitken 2012: 214). Also, in The Specificity of the Aesthetic, Lukács proposed the highly-intuitionist concept of Stimmung, or ‘atmosphere’. Here, the film sequence is conceived of as evoking a general ‘atmosphere’, or tone: a Stimmung. These atmospheric sequences succeed each other across the course of the film, ultimately cohering into final aesthetic unity of atmosphere, or Stimmungseinheit (103-4). Such intuitionist concepts also suffuse the writings of the other major realist film theorists. For example, Grierson’s notion of the ‘real’ as underlying the actual, his notion of Zietgeist,and intuitive understanding of the ‘absolute’ are all intuitionist concepts. Grierson was influenced by the ideas of the British neo-Hegelian philosopher W.H. Bradley, who argued that forms of religious and aesthetic experience were better able to comprehend reality because such forms of experience were essentially intuitive, (Bradley 1914: 175) and Grierson adopted this view when arguing that ‘The artistic faculty means above all the power to see…the hidden harmonies of man and nature’ (Aitken 2013: 44). As with Grierson so with Kracauer, who argued that the way to escape from a debilitating modern condition was through transcending abstraction and experiencing the world in its phenomenological richness through revelatory insight. Finally, André Bazin was influenced by the ideas of the French phenomenologist Henri Bergson. Amongst these ideas was that of ‘self-conscious instinct’ (Russell 1965: 758). Here intuition does not operate in the way that intellect does, through dividing up experience, but, instead, comprehends the experience as flux. Many of the above ideas will be discussed in greater depth in the next section of this Introduction. For the moment, though, this brief exposition serves to situate the major realist film theorists within an intuitionist paradigm. However, it will also be argued later that it will be both misleading and not enough to subsume these theorists entirely under an intuitionist label. The intuitionist paradigm must, therefore, be qualified and modified, particularly in relation to phenomenology, and that will take place in the conclusions section of this Introduction. Prior to that the relationship of the major realist film theorists to what has been established to be a central component of any realist theory: particularity as found in empirical experience and representation, will be addressed.

This section of the Introduction focuses on conceptions of empirical representation which influenced the major relist film theorists. These conceptions will be considered in depth with a view in the conclusions section of this Introduction to gathering them together into a reassessed model of theoretical cinematic realism.

Siegfried Kracauer’s belief that modernity was characterised by abstraction led him to assert that such abstraction could be reversed by close and meaningful focus on empirical perceptual experience and the aesthetic representation of such. Kracauer drew directly on the phenomenological notion of immersion within the Lebenswelt here. For Kracauer, close attention to immediate experience ‘redeems’ reality for the individual and leads to a greater understanding of the individual’s existential situation within the Lebenswelt. In addition to the idea of the Lebenswelt, which has already been covered in this Introduction, Kracauer’s theory of cinematic realism was also influenced by three related Kantian concepts: the ‘harmony of the faculties’, Naturschöne and ‘disinterestedness’, all of which are closely related to modes of empirical representation and experience. The ‘harmony of the faculties’ refers to a harmony between the ‘faculties’ of the ‘Understanding’ and ‘Imagination’. For Kant, the faculty of Imagination unites the sense impressions which human beings experience into various evolving structures and patterns whilst the faculty of the Understanding then applies higher-level regulative concepts and classifications to these. The ‘harmony’ of these faculties occurs when the Understanding seeks order and totality and also interacts with the Imagination in such a way that the latter also seeks meaningful formations and a sense of wholeness in the object of contemplation (Aitken 2007: 106). There is a dialectic at play here in which the Understanding, when seeking order and totality, stops the Imagination from becoming anarchic and engaging in what Kant refers to as ‘lawless freedom’, whilst the Imagination, regulated by an order-seeking Understanding, opens up the latter to new, diverse but still lucid possibilities (Aitken 1998: 126). Kant believed that this interactive dialectic between Imagination and Understanding underlies and shapes all cognitive activities and leads to the generation of knowledge. However, he also believed that, within aesthetic experience, that interactive structure does not lead to the generation of definite knowledge because aesthetic experience is concerned with feeling rather than concepts. This means that the knowledge which is garnered during aesthetic experience is indefinite in character. Within aesthetic experience, in which the harmony of the faculties is generally directed at an art object, the empirical also plays a crucial role, because an empirical array is inevitably present where the object of contemplation is a concrete object. Here, the empirically-constituted art object provides the foundational material and parameters for the Understanding and Imagination to seek an indefinite order and meaningfulness. However, and in a similar way, the contemplation of nature also provides such foundational material – though different parameters, and Kant refers to such contemplation of nature as an experience of Naturschöne. Naturschöne: ‘natural beauty’, or the ‘beauty of nature’, refers to meaningful formations and a sense of wholeness found when the Imagination and Understanding contemplate nature. Here, the harmony of the faculties is achieved through the experience of nature. In Naturschöne the empirical abundance of the natural environment enables the Imagination to freely explore diverse possible structures, formations and movements, and also enables the Understanding to shape and regulate and be affected by such exploration. Here, nature helps both Imagination and Understanding seek and establish a sense of order, pattern and wholeness which is enhanced by contact with the compound and indeterminate non-human environment. A dialectic interaction between the Understanding and the Imagination occurs here in the encounter with nature. Such a dialectic is also involved in the encounter with the art object, though there is a difference between the two. In the encounter with the art object, the concrete richness of the material art object provides a circumscribed empirical foundation for the interaction of the Imagination and Understanding. However, the empirical foundation for such an interaction provided by the encounter with nature is richer and more indeterminate than any art object could establish and circumscribed only by the viewing horizon of the spectator. There is a sense here of the experience of Naturschöne as providing the basis for more complex interaction between the Understanding and Imagination than can be afforded by the work of art, and this might also imply that works of art – including films – should be ‘nature-like’: should be largely indeterminate whilst leaving some space open for ordering activity. In addition to this ability to generate a more multifaceted interaction between the Imagination and Understanding, the experience of Naturschöne involves a re-enchantment of human experience in which the individual returns to a vibrant nature lost under the prevailing abstractions and conditions of modernity. Here, the experience of Naturschöne amounts to a resonant and animated experience of a nature full of what Kracauer calls meaningful ‘correspondences’; (ref) and also returns lost nature to the individual, creating a unity of experience linking man to nature. Here, the gap opened up within modernity between nature and the typical and degraded experience of nature is sealed and a sense of return to a more authentic and meaningful experience is established. It is, therefore, encounter with the empirical landscape which provides a foundation for the materialisation of a qualitatively enhanced synthesis of empirical experience, reason and intuition to emerge, and for a sense of re-enchantment and a unity of experience to occur. And, this also suggests that works of art, including films, should accord with the form of interaction between the Imagination and Understanding which occurs within the harmony of the faculties. Finally, it is unsurprising that Kracauer, a student of Kant, should turn to the notion of ‘disinterestedness’, a notion that, though, has also ‘probably been the single most important concept in the last three centuries of aesthetic theory’ (Collinson in Hanfling (ed.), 1994: 134). Disinterestedness refers to the notion that aesthetic judgment and the object of contemplation at which that judgement is directed should stand outside instrumental purpose and need. In the Critique of Judgement Kant argued that the ‘judgement of taste’: the judgement that something is aesthetically valuable, is not related to any interest on the part of the perceiver, but only to the free experience of the object of judgement: The judgement of taste is simply contemplative, i.e. it is a judgement which is indifferent to the existence of an object, and only decides how its character stands with the feeling of pleasure and displeasure (135-6). Disinterested aesthetic experience is what Kant calls ‘free liking’, and ‘pleasurable liking’. Kant thinks that such ‘liking’ may also be the ‘one and only disinterested and free delight’ because it lies outside of interest (136). The idea of ‘contemplation’ here also means something like an act of deep and long consideration, observation or admiration; and can involve both thoughtfulness and simply ‘looking at’ something. The only ‘interest’ involved here is a ‘looking-for-pleasure’ in order to experience pleasure. However, Kant argues that this is so deeply embedded in our cognitive existential make-up that it does not count as an ‘interest’ in the customary sense of the term as something related to ‘self-interest’ or personal advantage. However, disinterested aesthetic experience is not only free because it is free of such interest but also in that it is not constrained by the parameters of conceptual reason. Kant argues that the disinterested judgement of taste cannot lead to definite knowledge because it is based on feeling. Because it is based on feeling, and is unrelated to conceptual knowledge, the judgement of taste is indefinite in character. It is the product of an interaction between the Imagination and the Understanding which generates indefinite meaning grasped intuitively through feeling. So, we have an experience which is indefinite, is afforded through feeling, and cannot be rendered via language. Here, the Imagination and Understanding interact to generate indefinite, but harmonious feelings – the latter because harmony is intrinsically pleasurable. Freedom is involved here, but so, also, is order, and both ‘lawless freedom’ and domineering regulation are avoided (137). In addition to being ‘nature-like’ and according with the harmony of the faculties, therefore, the art object (including the film) should be free of interest, and not linked to purpose or intent; and all of this is additionally further indicated by a notion that Kant relates to the notion of disinterestedness: that of ‘purposiveness without purpose’. What Kant means here is that, in the encounter with nature or a work of art, patterns and arrangements are perceived, and there therefore seem to be ‘purposes’ evident in the sense of the patterns and arrangements being as they are through some cause or organisation. However, no definite purpose or meaning can be discerned. This indefinite purposiveness, when perceived in a landscape or work of art, is particularly important because it makes the Imagination and Understanding interact equivalently, and therefore causes both to engage in an activity which is law-like and free. Here, a meaningful sense of union is established with the art object or nature premised on the notion of purposiveness without purpose. These Kantian notions will be returned to later when an attempt is made to link them to a general model of cinematic realism underlying classical cinematic realism. Before that, however, the relationship of Lukács to the German philosophical tradition will be considered.

Unlike Kracauer, there are fewer specific theoretical influences from other theorists relating to the empirical that can be identified per se in the writings on film of Georg Lukács. Lukács was influenced by the German philosophical tradition in general, and by Kant and Hegel in particular, with the latter of those two having the greater influence. However, Lukács’ writings on film often combine these and other influences in various ways and change them in the process to the extent that few clear paths of influence can be traced. One consequence of this is that, unlike in the review of influences on Kracauer just undertaken, in which general philosophical conceptions were explored, it will be necessary here to first place a more directed emphasis on Lukács’ writings on films before considering such conceptions. A key empirical notion which arises in Lukács’ film writings is that of Geradesosein, which Lukács develops from Hegel, Engels and other sources. Geradesosein, or the ‘just-being-so’ of things, refers to the ability of film to capture an important aspect of human experience. Here, whatever we experience and whatever attitude we adopt towards such experience we also experience that which we encounter as materials which are perceived by us as existing in-and-for-themselves. Because the encounter with the just-being-so of things is an authentic aspect of human perceptual encounter Lukács argues that, in addition to other aspects of filmic representation, the medium should also attempt to portray this encounter. It is also because of this imperative that Lukács maintains that the relatively-autonomous image must be retained as ‘an essential element of…film art’ (Lukács 1981, II: 473). A further way of understanding Geradesosein, and also connecting the notion to broader conceptions, is to refer to Hegel, although Hegel does not use that term himself. In the Phenomenology of Spirit Hegel refers to the empirical particularity as the ‘this’ (Dieser): the immediate object of sense perception, or what Hegel also calls ‘sense-certainty’ (Desmond 1986: 21). However, Hegel does not regard the ‘this’ as an unmediated particularity but as a mediated ‘concrete universal’. The idea of the concrete universal is a complex one, has been widely interpreted by various scholars, and cannot be considered in depth here. Put succinctly for present purposes the notion suggests that every particularity is associated with a range of universals and cannot be separated from these. For example, when one views a tree one does not simply view the tree as a single entity but as one which is inseparably linked to a range of universals which ‘inhere’ to the entity; universals such as ‘woodenness’, ‘natural’, ‘greenness’, ‘shape’, etc. These universals inhere to our perception of the particular tree and are inseparable from that perception so that we cannot see the tree as a bare ‘this’. This is, epigrammatically, what Hegel means by the phrase concrete universal. In the Aesthetic, Lukács takes on board this conception of the concrete universal, but only to a certain extent. For example, in a chapter entitled ‘Besonderheit as an Aesthetic Category’ he sets out an account of inherence in which he asserts that relations and determinations are inherent to any particular manifestation of singularity as no one thing can be entirely separated from the determinations and relations associated with it (Lukács 1981, II: 232). However, Lukács does not go on from this to adopt the abstract idealism implicated by the idea of the concrete universal. Hegel’s argument led him and later interpreters to the position that universals not only inhere to a singularity but actually constitute it, so that all that really exists for us is an interactive network of universals and no foundational ‘substance-of-the-object’ can be identified (Putnam 1992a: 46-8). However, as a Marxist-realist Lukács was unable to accept such a relational model of meaning and he insisted instead on a correspondence model in which properties and relations inhere to a definite object modality, though, and as will be argued, a modality that is still not a singular ‘this’ but rather a ‘micro-totality. This emphasis on the identity-ness of the object – and in this case person - is clear from Lukács’ reference to Engels’ iconic 1885 ‘Letter to Minna Kautsky’, in which, according to Lukács, Engels insists that in the work of true realist literature ‘everyone is a type, but also simultaneously a single individual, a Dieser, as old Hegel would have expressed himself’ (Lukács 1981, II: 232). Lukács uses this assertion that a singularity is also a multiplicity to argue that inherence must be interpreted as referring to a situation in which relations and determinations do not overwhelm or make up the identity-ness of the singularity (Parkinson in Parkinson (ed.), 1970: 136). However, the question then arises as to what that ‘identity-ness’ consists of, and how it and the ideas of Geradesosein and inherence, relate to film. For Lukács, in terms of Geradesosein, the ‘object’ is first of all understood as that which is both perceived by and also impresses itself on the senses. By the experience of Geradesosein, the experience of the ‘this’, therefore Lukács refers to an encounter with an object in our experienced life-world in which the object looms up out of its various relations, contexts and connotations to be encountered as an entity per se apparent within our perceptual field. Here, the object-entity consists, firstly, of basic perceptual properties. A desk for example will consist, at a basic level, of shape, colour, size, etc. There is no ‘essence’ to the desk: no one substance that is ‘desk’. However, there are a number of cohering basic properties and relations between those properties which constitutes it as an object-entity. What, therefore, Lukács means by Geradesosein is a situation in which a cohesion of basic properties emerges out of the flux of the life-world to constitute a composite object, and one which can also then be scrutinised in further detail, both at this basic primary level, and at the level of secondary properties, which, to return to the example of the tree, would include such as texture, colour-gradation and pattern. The experience of Geradesosein then seems to be based on contemplation of the coherence of these basic and secondary attributes to constitute an ‘object’ which exists as object within our experience of the Lebenswelt. Though the ‘object’ as singularity does not exist per se, it does exist meaningfully as such for us. The idea of the object consisting of basic and secondary properties and relations with no essence also leads Lukács to define particularity (Einzelheit) as a ‘micro-complex’. As Lukács puts it, each particular possesses its own spheres of meaning: its own mini-grouping properties and relations (Besonderheit): ‘the Einzelheit has its own Besonderheit inherent to itself’. However, Lukács also argues that these micro-complexes inherent to the particular are latent until activated by particular acts of cognition and intuition: they are, as Lukács colourfully puts it, in a state of ‘undeveloped in itself imprisoned form’ (unentfalteten, in sich eingesperrten Form) - they are metaphorically ‘speechless’ (Stummheit) (Lukács 1981, II: 232). A distinction also has to be made here between man-made and natural objects within the Lebenswelt in relation to Geradesosein. Man-made objects will be more suffused with connotation, relation and properties, uses, expectations and purposes than natural objects. When we see a tree, for example, and focus on that tree, its basic and then secondary properties emerge more clearly and vividly than when we view a desk because the tree cannot be subsumed under use-value to the extent to which the desk can. Lukács refers to this experience of nature-based Geradesosein in the Aesthetic when discussing the ability of film to portray the natural world. Here, he argues that, in film, ‘a visible, sensuous and evident world emerges sui generis (Aitken 2012: 190). In the earlier ‘Thoughts Towards an Aesthetic of the Cinema’, he also expresses the idea more strongly when asserting that, in film, ‘The livingness of nature here acquires artistic form for the first time’ (184). Here, ‘livingness’ (Lebendigkeit) refers to the nature-based experience of Geradesosein. There were many reasons why Lukács wished to hold on to the idea of particularity in the Aesthetic. In addition to the Marxist-realist stance on object-identity just mentioned he was also influenced by Hegel’s contention that, whilst, in ancient times, abstract thought had been necessary in order to lift up humanity from immersion in concrete immediacy, in the modern world such abstraction had gone too far and there was now a need to bring knowledge back to the ‘concrete wealth of the world thereby to regain a fullness lacking to merely abstract thought’ (Desmond 1986: 20). He was also influenced by the Hegelian notion that true thinking meant bringing abstract thought to bear on the material realities of the world. In his 1957 work On Besonderheit as an Aesthetic Category (Besonderheit), which was later abridged to form a chapter in the Aesthetic, Lukács asserted that Besonderheit was a ‘prolegomena’ to the later Aesthetic, in the Kantian sense of that word. In the Prolegomena to any Future Metaphysics, Kant had argued that Hume had ‘first interrupted my dogmatic slumbers and gave my speculations in the field of speculative philosophy a new direction’ (Kadarkay 1991: 445). That new direction was towards the study of empirical reality, and represented a shift away from a scrutiny of abstract philosophical generalisation, towards an understanding of the particular and specific. As with Kant, in both Besonderheit, and the later Aesthetic, Lukács is concerned with identifying the specificity of the aesthetic. Besonderheit is a little-known work. Nevertheless it succeeded in arousing the wrath of the communist establishment when it appeared because its focus on what Lukács called the ‘dialectics of the particular’ was read as a metaphor for a need to both understand the specificity of Hungarian communism and reject more general communist models imposed from outside. In Besonderheit, therefore, Lukács is calling directly for a philosophical shift from a study of axioms to a consideration of particularity, and, indirectly, for a political shift from the Soviet model to a specifically ‘Hungarian road to socialism’ (445). As with Kracauer, these notions are returned to later when an attempt is made to link them to a general model of cinematic realism underlying classical cinematic realism. Before that, however, the influence of the French tradition on Bazin will be considered.