Interview with Mrs. Lakshmi Murari and Radha Chadha - Wife and daughter of Indian documentary film pioneer Jagat Murari

12/09/2015

L - Lakshmi Murari (as translated from Hindi by her daughter Radha)

R - Radha Chadha

1) Your husband, Jagat Murari, received his masters in cinema from the University of Southern California (USC) in 1947. Can you tell us why he went abroad to pursue such studies and how this particular training influenced his approach to documentary filmmaking?

L:The British government (India was still a British colony at that time) announced a scholarship scheme to send people abroad for postgraduate studies in various subjects. My husband, Jagat Murari, had already done his Masters in Physics at Patna University (Bihar). He had done very well – he stood first in the University and received the University gold medal. So he was selected for the scholarship scheme.

R:He felt that his background in physics would be useful in cinema, because cinema is like a combination of art and science. He went to USA in 1945 by ship. He did his masters in cinema at USC and came back to India in early 1948.

L:At USC, he trained in all aspects of filmmaking, not only documentary but also feature filmmaking. He also did an internship of several months in Hollywood.

R:I think his background differed from other filmmakers of that time, who joined the film industry without specific training and learnt filmmaking by experience. My father, Jagat Murari, and some other Films Division (FD) people who went abroad to study – colleagues like Mushir Ahmad, K. L. Khandpur, Ravi Prakash, V. R. Sharma – were among the first who were systematically trained in cinema. He studied different aspects of cinema, including direction, cinematography, production, script-writing, editing, sound. In fact, his masters thesis was on the technical aspects of sound, which came easily to him because he had a solid background in physics.

My father’s first Hollywood internship was with the film ‘Macbeth’ (1948) by Orson Welles, who was famous for having made ‘Citizen Kane’ a few years earlier (1941). Welles was a dynamic, explosive character, a true genius, yet there was a period after ‘Citizen Kane’, when he was struggling to find funding for his films. He wanted complete control over his projects but the big studios were unwilling. Then, Republic Pictures, best known for Western B-movies, agreed to make his film ‘Macbeth’. The condition was that Welles had to complete his film’s shooting in just 21 days, and that too on a very small budget. My father was looking for an internship at the same time, and it was very difficult for a foreign student to get one in a big studio. As luck would have it, Republic Pictures agreed to take him on as an intern. That is how he met Welles, and got the opportunity to learn from him.

Working with Orson Welles had a tremendous impact on Jagat Murari. I have read lots of his diary entries about the days he spent working with Welles and the many things he learned during the making of ‘Macbeth’. One thing he learned was that extreme creativity and meticulous planning can go together. Welles wrapped up shooting in 20 days – with one day to spare – thanks to excellent planning. My father always felt that planning is very important in film production, you can save precious money and complete the project on time. Planning in India’s film industry was notoriously poor at that time. So that was a strong lesson for him, which he stood by for the rest of his life.

2) What was Jagat Murari’s personal vision for the documentary film?

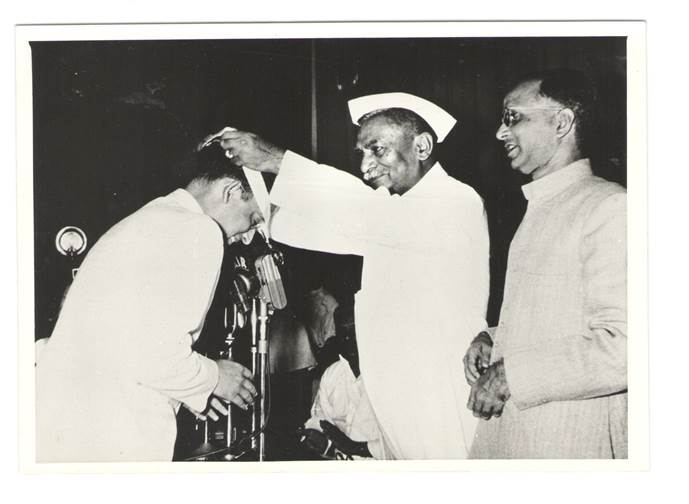

The President of India, Dr. Rajendra Prasad, presenting the President’s Gold Medal to Jagat Murari, director of the winning documentary film ‘Mahabalipuram’ in 1954. Minister of Information & Broadcasting, Dr. B. V. Keskar, is on the right.

From the collection of Mr. Jagat Murari

L:The first aspect is that he always wanted the film to be well made, it should be an excellent film. The second is that it should have an impact on the audience.

R:He was always after excellence, trying to make the best films he could within the parameters of FD. For example, when the national film awards started in 1954, Jagat Murari was the first person to win the President’s Gold Medal for his film ‘Mahabalipuram’, which he had made in 1952. It was a very special honor because all films made up until 1953 were eligible to enter for the awards, so ‘Mahabalipuram’ was competing with a much larger pool of films.

Concerning my mother’s second point, from what I know about him as a man, my father really felt that through the medium of film, he could make a huge impact on Indian people. This dear country of his was so poor, he yearned for it to grow, and he felt that through his films he could help its development and its people. Developing the country was a big theme that ran through his life. Even later in life, when he worked on building the Film Institute in Poona, foremost on his mind was that India must have the finest film school.

3) Jagat Murari joined Films Division right after its creation in 1948, and worked there as an in-house director and producer until 1961. How did he start working with this organisation?

L:My husband joined FD in November 1948, a few months after its creation. He knew he could get a job in FD, so he applied for a job there and got it.

R:There was some background to him joining FD. Before he went to America, the British government signed a bond with him that upon his return to India he would make documentary films for a government organisation. Of course, FD did not exist at that time, but all through his studies, he expected to work for a government organisation.

4) How did his job in FD evolve over the years?

L & R:He joined as a deputy director, then rose up the FD ranks to become a director, and then assistant producer. By the time Jagat Murari left FD in 1961 to go to Poona (to set up the Film Institute), he had written and directed 37 films. From 1959 to 1961, in his role as producer, he produced an additional 43 films.

5) What was his work method? How did he make his films and with whom?

L:He would be given a topic, and then he would research it and write the script himself. Then he would get the approval from FD to go and shoot the documentary. He would put his crew together, including his cameraman, his light technician, assistants etc. Although he lived in Bombay, most of his films were shot outside Bombay, all over India. He traveled to South India to make many of his films. ‘Mahabalipuram’ and ‘Madurai of the Naiks’ were made over there. He also went to remote villages to make ‘Our Original Inhabitants’, which is a film on Adivasis (tribal people) in India.

He worked with several cameramen, as FD would assign different cameramen for different films. Dara Mistry and Shanti Swaroop Verma, two of the renowned cameramen at FD, shot several films with my husband.

R:The commentators Sam Berkeley-Hill and Zul Velani, again very well-known for FD voice-overs, also worked with him a lot.

6) Some of Jagat Murari’s films made in the 1950s, including ‛Mahabalipuram’ (1954), ‛Bharat Natyam’ (1956) or ‛Madurai’ (1956) made a strong impact on Indian documentary cinema. Why were they noticed at the time and why are they still considered landmarks today?

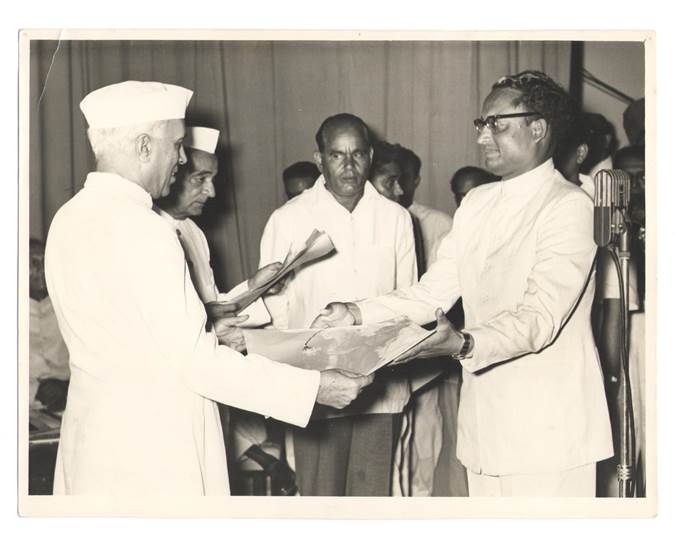

Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru presenting Jagat Murari the certificate of merit for the film ‘Wonder of Work’ at the National Film Awards function in 1956.

From the collection of Mr. Jagat Murari

L:‛Bharat Natyam’ is a major dance of South India, but at that time people did not know so much about it, so the film introduces and explains the dance to the general audience in an appealing way.

R:You have to see the film in its historical context, just a few years after India’s independence. India was young and far-flung, and Indians did not know much about their vast country. That might have been an important reason for the success of this film, as not so many documentaries like this had been made yet.

L:There were many temples shown in ‘Madurai of the Naiks’, and at that time, people were not able to go there to see the temples for themselves, although these holy places were important in their life. But through the film, they could see these places.‛Mahabalipuram’ also includes a lot of temples, and is also an important landmark in our history. I feel this is another reason why these films had such an impact on people.

R:I have watched these films recently. I watched ‘Madurai’ a couple of months ago and I have watched ‘Mahabalipuram’ many times. They are an absolute visual treat. Even today when I see ‘Madurai’, I feel that I am there, in the middle of the crowds of worshippers. It is just beautifully made and transports you there. ‘Mahabalipuram’ captures the beauty of the temples and statues, it is an ode to beauty. ‘Bharat Natyam’ shows a famous professional dancer. When this film was released, many film magazines wrote about it. All three films are about beauty and spirituality, which were very important to my father. He was always very moved by beauty.

My father made a very wide variety of films, but I think his cultural and scientific films had the most impact. Many of them were shown abroad, at film festivals, which may have multiplied the impact. ‘Mahabalipuram’, for example, was shown at the International Film Festival in Berlin in 1952. In the same year, it was shown at the Second International Art Film Festival in New York. In 1953, it went to the Edinburgh Film Festival. ‘Bharat Natyam’ was shown at Berlin and Edinburgh in 1956. ‘Madurai of the Naiks’ participated in the International Film Festival at Bergamo, Italy in 1958.

In this rare photograph, Chairman Mao Tse Tung and Premier Chou En Lai are seen with the Indian film delegation to China in 1955. Prithviraj Kapoor, the leader of the delegation, is standing between Chairman Mao and Premier Chou En Lai. Jagat Murari, the Secretary of the delegation is in the second row between Prithviraj Kapoor and Chairman Mao.

From the collection of Mr. Jagat Murari

His scientific films did very well too. ‘The Story of Steel’ won a certificate of merit at the Second International Festival of Scientific & Documentary Films in Venice in 1951, and it was shown at Cannes in 1952. ‘Wonder of Work’ won the first prize at the International Congress on Occupation Health in Helsinki in 1957.

Your readers in Hong Kong and China may find it interesting that two of Jagat Murari’s films, ‘Mahabalipuram’ and ‘Cave Temples of India – 1 (Buddhist)’, were shown in China in 1955, when a Festival of Indian Films was held there, and my father went as a member of the Indian delegation. This festival was considered an important step in bringing the people of India and China closer together in friendship. Jawaharlal Nehru, our first Prime Minister, personally briefed the delegation in Delhi. In China, the delegates met Chairman Mao and Premier Zhou Enlai – my father always remembered these meetings with great fondness. They traveled to several cities in China, and everywhere they were warmly received by huge crowds, and the Indian films were shown to packed houses. Films included classics like Bimal Roy’s ‘Do Bigha Zamin’ and Raj Kapoor’s ‘Awara’.

To go back to your question about why some of Jagat Murari’s films are considered landmarks, ‘Mahabalipuram’ was the first film to win the highest national honour, the President’s Gold Medal, and it also won a lot of international recognition, that is why it is considered a landmark. All three films – ‘Mahabalipuram’, ‘Madurai’, ‘Bharat Natyam’ – are cinematically beautiful, in fact, they are a celebration of beauty. They made a big impact on Indian audiences of the time, as they brought the culture of India to the masses. I think those are the main factors which make these films important.

7) Did Jagat Murari work with Jean Bhownagary during his time in FD and if so, what can you say about their collaboration?

L & R:Bhownagary was the producer of ‘Madurai’, which Jagat Murari directed. They had a very close relationship, they made several films together in the 1950s while Bhownagary was at FD. Their friendship carried on even after my father moved to Poona in 1961. Jean Bhownagary was from Poona, he had a home there, so whenever he came to Poona, they would meet.

R:From my father’s papers, I found that they exchanged letters and these letters carried on till the 1980s. So, I think they were not only filmmakers working together, but also close friends.

8) Jagat Murari left FD to join the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) in Pune, right after its creation in 1961 and worked there until 1971. Can you tell us more about the project behind the creation of this institute and the role Jagat Murari played in it?

L:The Film Institute started after the government bought the Prabhat Film Studio. It was a famous studio that had closed down. It had huge assets, including land, studios and equipment. The creation of the Film Institute was actually recommended in an official report in 1951, but it took 10 years to make it finally happen. The objective was to train filmmakers.

My husband Jagat Murari was there from the beginning, he did everything from making the course content, designing the syllabi, consulting other institutes from France or Moscow to get their input. He also taught the students. When he joined the Film Institute, he was the Professor of Direction. The actor Gajanand Jagirdar was the Principal, but in an unexpected move, Jagirdar resigned shortly thereafter, and my husband took charge of the whole Institute.

R:He decided to join the Film Institute early on in 1961, but the government procedures and FD handover took several months. During that period, Jagat Murari was already helping the Principal at FTII. Bombay and Pune are very close by, and he would travel back and forth. In fact, he was in Pune in July 1961 when the Panshet dam burst and Pune was flooded – he had come to interview students for the Direction course, but of course, the interviews were postponed. His role was to build that Institute almost from scratch and make it grow into a successful endeavour. In the 1960s, it trained amazing actors, directors, cinematographers, sound technicians – people like Jaya Bhaduri, Shatrughan Sinha, Rehana Sultan, Adoor Gopalakrishnan, Mani Kaul, Subhash Ghai, K. K. Mahajan, and many more who made a big impact on both the commercial and art film scene in India.

There was an initial resistance from the film industry to let all these trained people come in. My father made a huge effort to break that resistance and promote the FTII alumni, he held trade fairs to showcase student films and encourage regular interaction with established filmmakers.

The Film Institute grew and Jagat Murari expanded the courses and staff year by year. There were five courses initially – Direction, Screenplay Writing, Motion Picture Photography, Sound Recording & Sound Engineering, and Film Editing. In 1963, he added the Acting Course, raising the student capacity to 70. Foreign students were welcomed in 1965-1966. The CILECT (International Association of Film & Television Schools) affiliation came soon after. 1969 was a landmark year – UNESCO selected the Institute, then barely eight years old, as the place for TV training in India, stating in its report that the Film Institute compared most favorably with any film school in Europe or America. In 1971, it was renamed as the Film & Television Institute of India. It was an amazing first decade.

My father worked on every aspect of the Institute, right from the buildings, equipment, teaching programme, administration, production of films. Every student had to make a diploma film, as well as several short exercise films. I think his FD experience was very useful, since he had worked as a producer turning out dozens of films a year. So, he knew how to manage the production of a large numbers of films. Jagat Murari also taught many courses, including documentary filmmaking, film direction, ideas workshops. He was the teaching principal of the Institute. So, this institution was his baby, his love. He was very happy that it did so well.

9) What were Jagat Murari’s connections with the Indian art/parallel cinema? Can you relate his personal vision for the documentary film with the aesthetic and social aspirations of this new generation of art filmmakers?

L:A lot of Indian art films were made by the Film Institute graduates. Many of the key players – directors, actors, technicians – were trained at the Film Institute. I would say 70 to 80 percent of the players came from the Institute.

R:There were directors like Mani Kaul, Kumar Shahani, Adoor Gopalakrishnan. Actors like Shabana Azmi, Naseeruddin Shah. Cinematographers like K. K. Mahajan and A. K. Bir. There were many films funded by the National Film Development Corporation. A very large percentage of those films were made by or benefited from the participation of Film Institute graduates. They were willing to work with less money, because they were fresh out of the Film Institute. And a lot of the films they made won awards.

L:Jagat Murari’s own vision was that there should be all kinds of cinema represented in India. He was a supporter of ‛good cinema’, and ‛good cinema’ could be translated either as an art film or as a commercial film.

R:Jagat Murari definitely encouraged the art cinema movement. The students from the Film Institute played such a prominent role in Indian art cinema, because of their training and the emphasis placed on creativity and self-discovery. The kind of films they were exposed to also played a part. Their daily screenings included films from everywhere in the world, and these films were used as teaching material, including the French New Wave, Italian Neo-Realism, Russian masters, Japanese, Swedish, and of course, Indian cinema. It was mouthwatering fare – De Sica’s ‘Bicycle Thieves’, Godard’s ‘Breathless’, Eisenstein’s ‘Ivan the Terrible’, Kurosawa’s ‘Rashomon’, Ray’s ‘Pather Panchali’, Bergman’s ‘Strawberry Fields’ – this is what daily screenings were made of.

At the same time, my father felt that art cinema had a very limited audience in India. There were a couple of reasons to explain this. One reason was that the normal distribution circuit would not show such films, and they would only be shown in film festivals [or by film societies]. Some art films were never screened to an audience, they just sat in their cans. The second reason was that art cinema did not appeal to the common man, who found it dull and boring, and that is why no distributor was interested as it was not viable from a business angle. So, my father felt there was a different role for art cinema, that of artistic expression, of experimentation, of spurring new directions, all of which were crucial for the growth of cinema as a field of art. But equally, he felt that a film is complete only when an audience sees it. So he was as much in favour of commercial cinema, but he felt that commercial films made at the time were not good enough, he wanted better direction, better acting, better photography, sound and editing. He wanted more original stories rather than copying stories from Hollywood or repeating the same formula. He thought that such improved films would be understood and seen by the masses.

Here you have to understand where he came from. With FD, he worked for 13 years, all over India, spending time in villages and remote areas. He knew the Indian people, their aspirations, which he understood from his experience on the ground. He lived with them. Every time he spent 3 months shooting in small towns or villages, he looked at factories, schools, how people lived their lives and he really understood them. And he knew one thing for sure: most people were not interested in art cinema, they wanted to be entertained.

Jagat Murari understood the diverse audiences of India, from art cinema aficionados to the poorest man with no education, and to those in-between – the middle class people. He understood the power of cinema in shaping our newly independent country. He stood for ‛good cinema’ in whatever shape or form, whether art or commercial. There was a lot of tension later on at the Film Institute, because there was a sense that only films of the ‛New Wave’ kind should be made, even though such films were only seen in a few film festivals and film societies, which is wonderful, but they missed hundreds of millions of Indians who could also benefit from better cinema.

There was also the very practical aspect of making money – he wanted his students to earn a living, which was hard enough in commercial cinema, and even harder in low-budget loss-making art cinema. He wanted his students to be financially successful, he could not bear to see them impoverished. He was always canvassing for them, trying to get them jobs, whether in the film industry, in television, in government film organisations, or in film education.

10) Jagat Murari was also involved in the creation of the National Film Archives of India (NFAI) in Pune in the early 1960s. What was his contribution to this project? What place was attributed to documentary films in these new archives?

L:The objective was to preserve the films made in India or acquired from abroad. Initially, the physical location of the film archives was inside the Film Institute, because the Institute needed a large amount of films for teaching the students, so they started buying films.

R:Yes, the archives began as a subset of the Film Institute. They needed a good film collection for the teaching programme of the Institute, so in 1962, the Government asked Jagat Murari to start work on setting up the NFAI. He set the vision for this new organisation, shaped the objectives, drew up the plans, got the funding. The Archives opened formally in 1964, with a small office within the Film Institute. It used the Institute’s film vaults and theatres for screening. My father did double duty – he was the head of the Film Institute and also the head of the Archives till 1967.

But his vision was always to have the Archives stand on their own legs – to have their own building with film vaults, projection theatres, viewing rooms with Steinbeck viewers, film checking rooms, a book library, office complex – and he set the course for that.

One of the Archives’ objectives was to develop Indian audiences’ taste for art cinema, which relates to your previous question. It was felt that with exposure to good films from all over the world, a broader section of the Indian audience would develop a taste for better cinema. Film societies of the 1950s had made a start and the Archives were supposed to encourage this movement by providing access to landmark films. He managed to get film appreciation courses started, the first one was held in 1967 with the noted British critic Marie Seton. These courses were open to film lovers among the general public, and they continue till today.

As for the place attributed to documentary films in NFAI, I would say that they included a lot of Indian documentary films, as well as international ones. They chose films of some repute, award-winning or historical landmarks. There is Sergei Eisenstein’s classic ‘Battleship Potemkin’. There is Bert Haanstra’s poetic documentary ‘Glass’. There is Basil Wright’s ‘Night Mail’ – in fact, Wright came to the Institute to teach. Some of my father’s films like ‘Mahabalipuram’ are also kept in the Archives. All of them were used to teach students of the Film Institute. Documentaries definitely became a big part of the Archives.

11) Jagat Murari has been involved in the main public institutions developed over the 1950s-1970s to support a certain kind of Indian cinema. How would you define this state vision and to what extent did Mr. Murari align or depart from that vision?

L:These organisations were run by the government, my husband went wherever he was posted or transferred, it was done by government order. But wherever he went, his objective was to build a very good institution. He always wanted the best and worked very hard to make it so.

R:Jagat Murari definitely had three ‛babies’: the Film & Television Institute of India in 1961, the National Film Archives of India in 1964, and the Film Festival Directorate in 1973. And he nurtured and nourished them like a doting parent. He was always after excellence.

I think the government tried to promote a higher level of artistic cinema, as against the trite song-and-dance formulaic films churned out by the commercial film industry. The early people of the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, from Nehru’s time, were highly educated and had a high sensibility in terms of music, cinema, arts, literature. They had this vision to improve Indian cinema and therefore built these institutions to tackle the problem from different angles. The Film Institute was to train directors, technicians, actors, who would then go into the industry and lift the standards of Indian cinema, or alternatively make high standard art cinema. The National Film Archives’ purpose was to collect and disseminate excellent films, so that ordinary people could have access to it, and which over time would influence their taste for better cinema. The Film Festival Directorate had the same objective to bring world cinema to the Indian audience, and to celebrate and highlight good cinema. The Film Festival Directorate also managed the annual National Film Awards programme, which again had the objective of recognising and encouraging good cinema from all regions of India. So, I would say that uplifting film quality was the state’s vision underlying these three institutions that my father built.

FD’s objective was different – it was to develop India through communication, especially in the 1940s and 1950s, since there was no television yet available in India. So, FD played a role here in terms of informing, educating, providing the cultural glue for a new country.

12) Mr. Murari’s films made in the 1950s remain his most acclaimed to this day. But did he continue making or producing films later in his career? If so, could you tell us more about his later films?

L & R:The 1950s was a very productive period for Jagat Murari. He made dozens of films for FD during that decade, and as we have talked earlier, many of them won recognition. Between 1959 and 1961, his role at FD changed to that of a producer, and he supervised the production of another 43 films, plus, when he left, there were 13 films in an advanced stage of production. So, he was involved in lots of films.

Then, he went to the Film Institute. Again, there was a big film production programme, because they made a lot of student films. He was the producer of all these films. In the first decade itself, over 160 short films were made, mostly by students, and a few by staff members.

L:In the initial days at the Institute, Jagat Murari’s involvement in filmmaking was very deep. They were very short of staff, so they were like a close-knit family doing everything and helping the Institute to grow. I remember a documentary he produced about Poona, it was called ‘One Day’, made in collaboration with IDHEC (French film school), which won the Golden Gate Award at San Francisco International Film Festival in 1964. It also won a certificate of merit at the National Awards in India. It was also shown at Edinburgh and Sydney festivals in 1965.

In 1972, he went back to FD for a short stint. Again he produced films there. His film ‘Homi Bhabha - A Scientist in Action’ won the National Film Award in the Experimental Category in 1973. Another film from this period, ‘Lost Child’, based on the story by the well-known Indian writer Mulk Raj Anand, also won recognition.

Then, he was at the Film Festival Directorate, and it was the only time in his professional life when he was not directly involved in film production. In 1976, he went back to the Film Institute and retired from there in 1979. From 1979, he returned to his first love, documentary filmmaking, working as a producer, director and scriptwriter and made 10 films, some for FD, some for other organisations. He was still behind the camera at the age of 70+. After that, he continued to be involved in the film field, but more as an advisor.

13) Mr. Murari’s films received several national and international awards. At the international level, why do you think his films were noticed and appreciated?

L:Yes, his films won many awards. At the international level, whether at Cannes, Berlin, Venice, Edinburgh, Locarno, his films competed with other countries’ films and managed to win recognition. Just to be selected in these festivals means the film met a certain cinematic standard of excellence.

Why were they appreciated? His films always portrayed different aspects of India, and maybe the international juries and audiences enjoyed the beautiful and unusual sceneries, the people, the culture. But I think he went beyond that – there is a certain spirituality in India and he managed to capture that spirituality on film, that is what makes his films special. He was a very sensitive man, he always had a strong spiritual connection, and I think that somehow showed up in his films.

14) Overall, what would you say constitutes his main contribution to Indian documentary cinema?

L:Jagat Murari’s most important contribution would be the creation of the Film & Television Institute of India – he worked at it from scratch and turned it into an amazing place for producing the best kind of cinema, whether feature films or documentaries, and it was globally recognised as a centre of excellence. It is his most impactful contribution.

Secondly, he made very good films, and some of them are highly recognised and received both national and international awards. Thirdly, his contribution was that he documented the country’s culture, scenes and spirituality in a very good way. Even when you watch ‘Mahabalipuram’ today, which was shot more than 60 years ago, you still can feel it. He did it in a way that is enduring and stands the test of time. It captures and documents that era. He gave expression to the spirituality or ‘soul’ of India from that initial period after the independence of India.

R:I agree, my mother has said that so well. He did document the soul of India and he did it with sensitivity and emotion.

To expand on her other point about the Film Institute being his most impactful contribution, Jagat Murari not only made films, he made filmmakers. They in turn made thousands of films. He created a certain culture at the Institute, a filmmaking ethos, a thirst for excellence, a grounding in India, the itch to break moulds and experiment, the magic of telling a story and holding an audience rapt, and through it all the quest for your own distinct creative voice. In some intangible way, he left his stamp on all these filmmakers. And all together, these filmmakers had a much stronger impact on Indian cinema than he could have had on his own. He was very proud of each one of them. They were like his own children and he was always fighting for them, even after his retirement, even to the end, they occupied a large space in his heart.

- Evey Shen (2015)