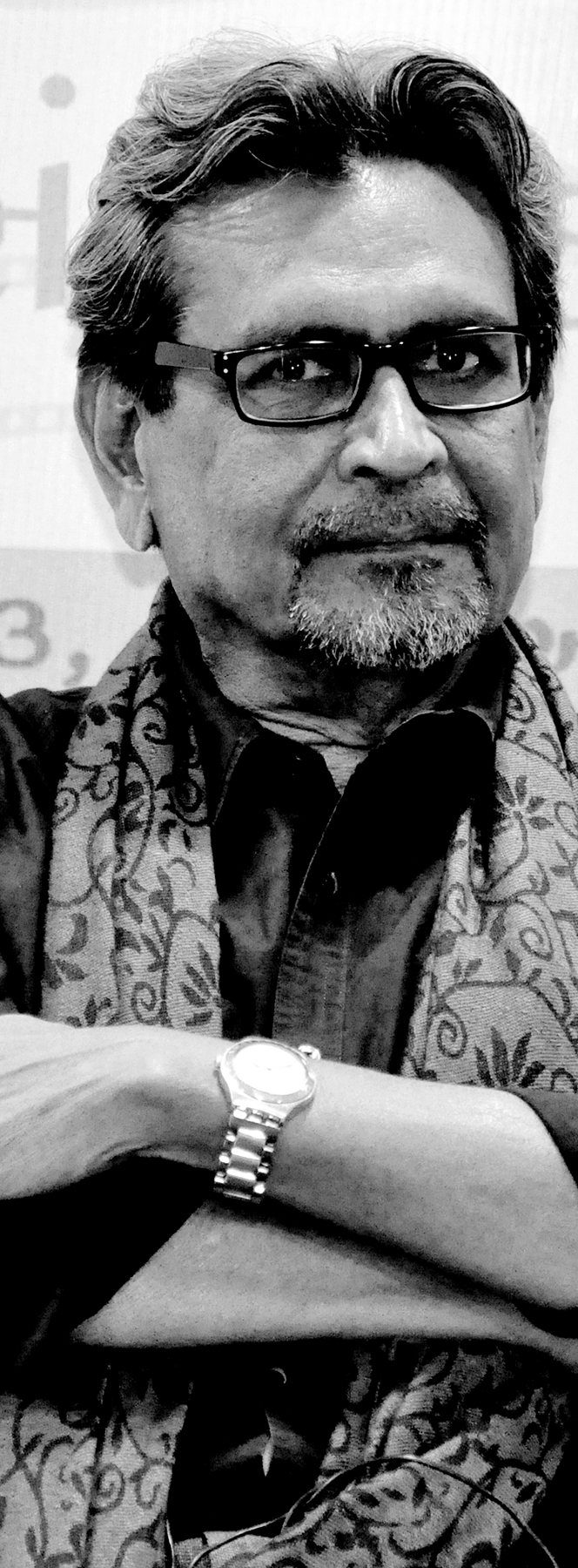

Interview with Amrit Gangar - Independent film scholar and curator

19/01/2015

1) Knowing that in India the documentary film and art cinema both came out of government decisions (and not from filmmakers rebelling against the domination of commercial cinema), what were the specific official relationships between the Films Division and art film institutions over the period from 1948 to 1975?

It started in the colonial times, with the British establishing the Information Films of India (IFI) during World War II for war propaganda purposes. This is how they wanted to use war documentary films. IFI was established by the British and then the Films Division carried on the legacy. Films Division made the screening of their documentary films in theatres and cinema houses compulsory. These were all colonial found legacy, which one could not shrug off. After India’s independence, Prime Minister Nehru recognized the importance of cinema or film medium, which was not the case for other leaders, especially Mahatma Gandhi, who never liked cinema in that particular context and time. Nehru had different views, he was inspired by Lenin and followed the Soviet model in a way. Hence, the Films Division became the largest documentary, newsreel and animation-making body.

Post-independence, the population of India was highly illiterate. Nehru thought that cinema should be used as a teaching medium to inculcate civic sense and civic education among the people. Around that time, he invited a Canadian filmmaker, Norman McLaren who was from the National Film Board of Canada, to help the Films Division. He was a great filmmaker and animator. Further, John Grierson also had an important role in shaping up the Films Division. The Films Division started making documentaries with the agenda of propagating the ruling government party, obviously because it was part of the Central Government’s Information & Broadcasting Ministry. Nehru gave a lot of space to the Films Division to carry out experimentation and also subjective filmmaking practices. Post-1960, a few more film institutions were born in India such as the Film Institute (now known as the Film & Television Institute of India, FTII), the National Film Archive of India (NFAI), the Film Finance Cooperation (FFC, now known as the National Film Development Corporation, NFDC), the Children’s Film Society of India (CFSI) and various other cultural bodies.

FFC did not take up film distribution. Later, NFDC was supposed to take this role by building a chain of small theatres. This did not happen immediately, but after the 1960s, it started and followed the national government policy. For various reasons, the envisioned national chain of small theatres what you call 'art house cinemas' never came into being. After that, the Emergency happened in India resulting in many things. I would argue that fundamentally, the new film movement in India was unlike the French New Wave movement. Here in India, it was one individual, and that was Indira Gandhi, who actually thought of instituting the FFC, which eventually started the Indian New Wave (which was again a label created by the media). Indira Gandhi was then the Minister of Information & Broadcasting and within her capacity she thought of funding the young alumni of the FTII through FFC. Such state funding was an enlightened decision, I think.

The Film Institute agenda was to feed the film industry with trained technicians, so that the Indian film industry (now mistakenly known as 'Bollywood') could improve in its content and form. S. K. Patil, then in the Central Government, under the instructions of Nehru, headed a Film Enquiry Committee, which aimed at imbuing a certain vision to the national film policy. As India is a continent-sized country with many languages, how can one deal with a common policy? The Federal Indian Constitution has three basic lists, viz. the Union List, State List and the Concurrent List. The last one applies to both States and the Union. Certain aspects related to cinema (e.g. censorship) are placed under the Union List, while others are placed under the State or Concurrent Lists. To my mind, an essential dichotomy arises when cinema is placed under the policy, administrative and executive purview of the Information & Broadcasting Ministry. Personally, I think cinema could neither be information nor broadcasting. In India, to my knowledge, Kerala is the only state where there is a ministry for cinema. No other in India state has this. I am of the opinion that the 1975 internal political Emergency had impacted the documentary film in India, and now the so-called globalization and technology are greatly impacting the young minds.

Within the Films Division, people such as S. Sukhdev and Loksen Lalwani were politically conscious even while remaining under the government set up, and they made some documentaries that are referencing and reflecting those times quite strongly, and controversially too. The Films Division was offered to run television, but they declined at that time, as I think retrospectively, for the lack of adequate vision and confidence, or for the lack of theoretical and practical comprehension between cinema and broadcasting, which was difficult for a filmmaking body such as the Films Division. Television was total broadcasting, which was the thought process at that time.

Eventually, politics and national vision all came together along with negligence and apathy, but the major and more palpable impact on the Films Division was technology and the way it went on to co-opt mindsets in bureaucracy and dealing with the inherent ruling party tensions and political priorities, rules set over decades were difficult to change.

- Dr. Camille Deprez (2015)